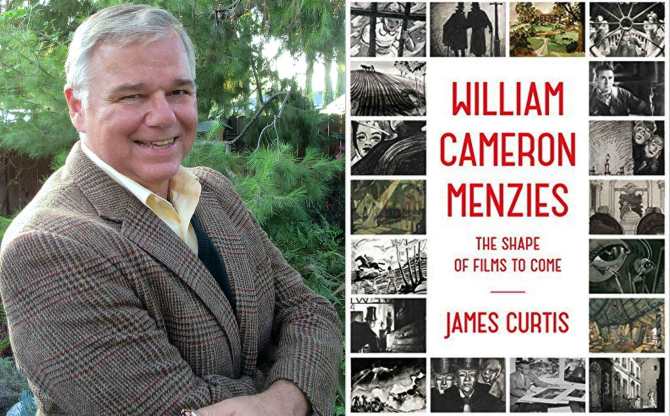

An excerpt from the new book by James Curtis.

Have you ever marveled at the “look” of certain movies? The art direction creates a memorable world. For example, The Son of the Sheik……

William Cameron Menzies’ original rendering of Ahmed’s desert retreat for The Son of the Sheik (1926). Economies scotched the design, a shame considering it would be Rudolph Valentino’s final film and a formidable commercial success. (courtesy of Pamela Lauesen)

Or both versions of The Thief of Bagdad, Things to Come, Foreign Correspondent, For Whom the Bell Tolls, the Dali inspired dream sequence in Spellbound, The Pride of the Yankees, It’s A Wonderful Life, Around the World in 80 Days, the childhood paranoia guilty pleasure Invaders From Mars, Duel in the Sun and, of course, Gone With The Wind.

A soaring pattern of ornate grillwork stimulates interest in Douglas Fairbanks’ midnight approach in The Thief of Bagdad (1924). “They let me take one detail and feature the devil out of it,” said William Cameron Menzies. “That’s the way to get effects into pictures–height. That’s the one dimension that lets loose the imagination.” (Courtesy of the Menzies family collection)

All of these have the influence of William Cameron Menzies as either Art Director, Production Designer or Director, sometimes uncredited when the films were released.

“He was the consummate designer of film architecture on a grand scale, influenced by German expressionism and the work of the great European directors. He was known for his visual flair and timeless innovation, a man who meticulously preplanned the color and design of each film through a series of continuity sketches that made clear camera angles, lighting, and the actors’ positions for each scene, translating dramatic conventions of the stage to the new capabilities of film. (1)

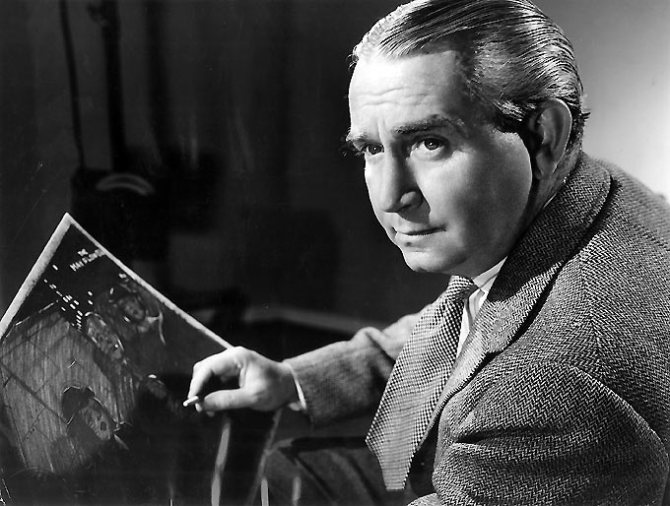

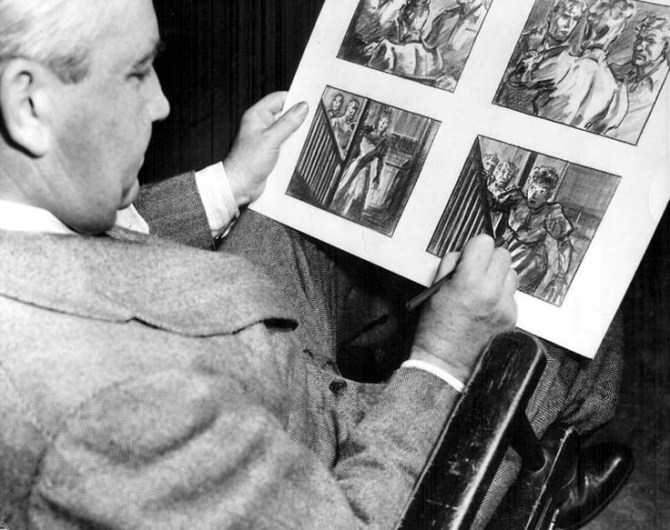

William Cameron Menzies poses with artwork developed for The Devil and Miss Jones (1941). (Photo courtesy of James Curtis)

In 2010 the insightful film writer David Bordwell wrote “William Cameron Menzies was a wunderkind. He started working on films in 1919 when he was twenty-three; ten years later he won an Academy Award. By the time he died in 1956, he had participated in over seventy films. Why has nobody written a book about him?

Don’t look at me. After several years sporadically tracking his career, I’m aware that this is a mammoth task.”

Finally that task has been taken up by James Curtis, known for his terrific (and definitive) books on Spencer Tracy, W.C. Fields, Preston Sturges and James Whale. After years of research he has completed William Cameron Menzies: The Shape of Things to Come complete with rare illustrations and photographs.

“Interviewing colleagues, actors, directors, friends, and family, and with full access to the William Cameron Menzies family collection of original artwork, correspondence, scrapbooks, and unpublished writing, Curtis brilliantly gives us the path-finding work of the movies’ most daring and dynamic production designer: his evolution as artist, art director, production designer, and director. Here is a portrait of a man in his time that makes clear how the movies were forever transformed by his startling, visionary work.” (1)

On Sunday, May 22 the American Cinematheque in Hollywood will feature the swashbuckling adventure comedy The Beloved Rogue (1927) with live musical accompaniment followed by a discussion about Menzies featuring James Curtis. Details here.

EatDrinkFilms is proud to offer an excerpt from this new book, William Cameron Menzies: The Shape of Things To Come that will surely intrigue any lover of cinema, design and art. This chapter tells the story of his extraordinary work on creating the burning of Tara in Gone With The Wind. Menzies was named Production Designer, a job title created by David O. Selznick for his Oscar-winning work on the classic. (A video clip of this sequence can be viewed at the end of the excerpt.)

Chapter One — Atlanta Burning

Preparations for the inferno had been under way for weeks when the night of December 10, 1938 finally arrived. Culver City, home to the RKO-Pathé Studios, had never seen anything like it. On a cluttered patch of land due south of the main lot–called “Forty Acres” but only 28 acres in actual area–a crowd of some 250 awaited nightfall with a palpable sense of anticipation and a little dread. Arrayed before them were the broad makings of the Atlanta rail yard as it would have appeared on the night of September 1, 1864, when a Confederate ordnance train was torched by fleeing troops, setting off a series of explosions that shattered every window in the city. The life-size recreation of this event, a scene that would normally have been accomplished in miniature, would mark the start of filming on the most eagerly anticipated movie of the decade.

Bill Menzies, clad in overcoat, sweater vest, and one of his trademark bow ties, was attending to details, his whitening hair glistening under the weak afternoon sun. He lit a Lucky Strike, one of the dozens he would smoke that day, and continued dressing the foreground, a gang of studio grips at his command. Strategically positioned around him were six Model D Technicolor cameras–all that were available–and two black-and-white cameras to shoot silhouettes and promotional footage. Two of the color cameras had been dedicated to recording the fire in widescreen, an effect producer David O. Selznick wanted for the first-run houses and the New York World’s Fair.

The spectacle entailed considerable risk, as the studio was surrounded by a residential neighborhood and had already endured a devastating fire in the mid-1920s. It was Menzies’ idea to burn some of the standing sets on the back lot when he learned they would have to be cleared for the construction of a massive brick car shed–the best known of Atlanta’s wartime monuments–and the fictional plantation house, Tara. He enlisted studio production manager Ray Klune in the effort to convince Selznick of the viability of the plan, over the fierce objections of M-G-M studio manager Eddie Mannix, who predicted the burning of the sets would not prove to be of “any substantial photographic value” in the Atlanta fire sequence and instead wanted Tara built on his own lot two miles away.

In collaboration with Klune and unit art director Lyle Wheeler, Menzies had studied the back lot and selected as kindling leftover sets from the Biblical epic The King of Kings. They fitted these with profiles and false fronts that suggested period warehousing, a water tank, a foundry, and populated the foreground with tracks, a string of freight cars, and packing crates of Enfield rifles, ammunition for Napoleon and Blakeley guns, and fixed cartridges. Weathering on the brick red cars had been accomplished with skilled brushwork and augmented with scrupulously authentic markings–W.&A.R.R., A.&W.P.R.R., M.&W.R.R., and GA.R.R. A gigantic wall, used in the Skull Island scenes of King Kong, was similarly dressed, cut from its supports, and laced with cables that extended down through a metal pulley block and several hundred feet to a powerful tractor.

Note the size of the Technicolor camera in the rear left

Now, with darkness approaching, Menzies intently made last-minute arrangements of the foreground details, darting from one camera position to the next, adding disabled field pieces of the proper vintage, some old wagons, discarded furniture, piles of cross ties, and, at one crucial point, a mud puddle. A miniature of the redressed sets had been constructed and the camera positions worked out in advance. “We planned the whole thing sort of as a football rehearsal,” Klune would later recall.

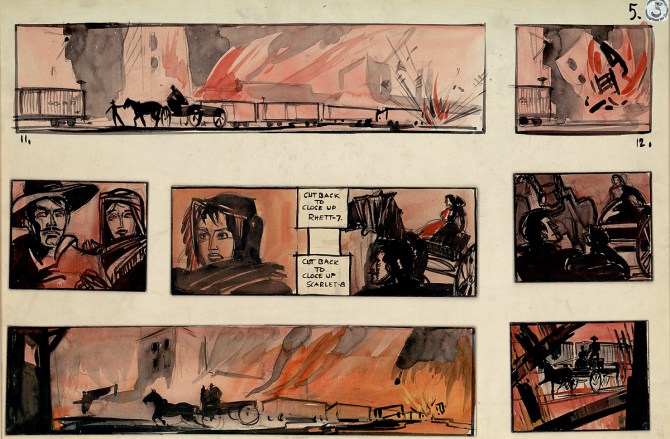

Working with screenwriter Oliver H.P. Garrett, Menzies had prepared an amplified script of the fire sequence and a detailed continuity that visualized the entire episode in 33 drawings: “For all scenes marked ‘Transparency,’ it is proposed we will shoot backgrounds for those on the night we shoot the fire. For all scenes marked ‘Cosgrove Split Screen,’ we will shoot the sky material that night, and scenes not marked ‘Transparency’ or ‘Split Screen,’ we will shoot straight with the real fire as background.”

Initial estimates called for 100 extras (50 soldiers and 50 civilians) but then Menzies and playwright Sidney Howard (the original scenarist) reasoned the town would probably have been abandoned by nightfall, and other than a few roughs, sentries, and straggling soldiers, Rhett Butler, Scarlett O’Hara, and the others would have been the last of the refugees. Director George Cukor agreed that this would add a sinister note to the scene, and suggested a few other changes to “increase the feeling that they are trapped in the fire, to have the fire behind them and, as they drive into the foreground, a burning beam falls in front of the horse, forcing them to turn off. Added to the business of losing control of the horse, this gives added justification as to why they are forced to drive through such an intense fire.”

Selznick reviewed these suggestions and sent word for Menzies to make new sketches “with particular emphasis on a constantly mounting violence in the shots and the fire getting greater and greater as [Scarlett and Rhett] drive through the streets, climaxing in the panoramic effect* on which we are working.” Menzies’ revised script and boards for the sequence were delivered on December 2 and rehearsals began promptly–first on the model, then on the lot itself. A final run-through was conducted on Friday, December 9. Fire tests were made on foreground structures, and light meters were held at various distances. Both of the stunt doubles for Rhett Butler, each clad in light linen suit and panama hat, were put through the same set of actions, with bits of physical business worked out between the horses and the drivers as they went. A chill wind blew ominously.

* Black-and-white experiments had been conducted with an anamorphic lens, which compressed the image and allowed the camera to capture more picture information, but Selznick was advised it wasn’t feasible to use such a lens with the Technicolor process. Cinematographer Winton Hoch then figured out a way of achieving the effect with two cameras and a mirror.

Storyboard by William Cameron Menzies for the Burning of Atlanta scene in Gone With The Wind, ca. 1939. (courtesy Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin)

In working out the logistics, it was decided that instead of changing lenses–which, according to Klune, “was a brute of a job on those Technicolor things”–the cameras themselves would have to be moved. Positions were marked on the miniature and numbered sequentially. “We’d move the camera from position one to position five–different lenses on each camera because we wanted to get a medium shot, a long shot, and a close shot from almost every position.” Since two of the cameras were allocated to the widescreen effect, and a third was a new high-speed camera designed to catch the collapse of the burning wall in slow motion, just three were left to record the action with conventional Technicolor lenses. Each of the six cameras would be assigned a crew of three–supervisor, operator, technician–responsible for making the specified shots according to Menzies’ drawings, re-loading the camera after ten minutes of film had been exposed (a complicated process involving three discrete film elements), and moving the outsized camera from one position to the next–all while the fire raged before them.

Given the fact it would be impossible to stop the fire once it had been started, Klune turned to a man named Lee Zavits (“the best special effects man in the business”) to devise a way of at least slowing its progress and affording the company some measure of control. Zavits designed a network of pipes studded with nozzles that could deliver fuel to the flames or dampen them as needed. Three 5,000 gallon tanks fed the system with centrifugal pumps. Two of the tanks contained a mixture of gasoline and distillate; the third was filled with water.

Carbon arcs, white and red-gelled and some amber, were mounted on tall platforms and trained on the set. Positioned at a microphone in the center of it all was Eric Stacey, assistant director and the man responsible to Menzies, Klune, and, ultimately, Selznick, for ensuring that everything went smoothly. Off to one side were three identical horse-drawn farm wagons and two sets of doubles representing the characters of Rhett and Scarlett. Dummies filled in for other characters: Scarlett’s sister-in-law Melanie; her baby Beau; and the excitable house servant, Prissy.

Though tests had already been made with a new higher-speed version of the notoriously slow Technicolor film stock, an item was planted in the Venice Evening Vanguard advising the local citizenry that “tests of fire and smoke such as would be needed for the burning of Atlanta sequence” would take place that night, with the hope of minimizing the number of onlookers eager to witness the official start of the film. Menzies and Klune anxiously followed the weather in the days leading up to the event, and on Friday evening, when the go/no-go decision had to be made, the official forecast read as follows: “Heavy ground fog from sundown on. May lift 100 feet or so during night. Horizontal visibility less than one-half mile.” It would be imperative to get all the necessary shots before the fog intervened. The best news of all: NO WIND.

There was scarcely a twilight. It was dark by five o’clock, and work lights illuminated the orderly bustle of property men, cameramen, and electricians as they made their final preparations, casting long shadows as they went. Off-duty firemen from M-G-M and the Culver City Fire Department stood by, ready to take control if the blaze got out of hand. Their ranks were swelled by personnel from the Los Angeles Fire Department, who ringed the area with equipment. Just when everything was in position, supper was announced. The guests made their way to a paved area of the North African village built for The Garden of Allah, lined up cafeteria style, and proceeded to gorge themselves on spaghetti, turkey à la king, baked potatoes, salad, pie, and coffee. Making their way back through the adobe dust, most could be observed munching on big red apples.

Now came the wait. Around 7:30, a limousine carrying Selznick and Cukor arrived on the scene. They huddled with Menzies, Jack Cosgrove, the head of the special effects department, Harold Fenton, head of construction, Harold Coles, the property manager, Lee Zavits, Klune, and Yakima Canutt, the principal stunt double for Clark Gable (who would be playing Rhett Butler in the picture). Then Selznick nervously worked the crowd, greeting some and asking others if they thought it would come off properly. All of the studio’s department heads were present, and many had brought their wives for the show. Menzies’ wife, Mignon, wasn’t among them. Not wishing to distract him–and never particularly comfortable around people in the industry–she chose instead a view of the Selznick lot and Ballona Creek from the parking lot of the Westside Tennis Club, where she sat alone in her nine-passenger Cadillac.

Ray Klune went to the microphone and gently asked the crowd, which included the producer’s mother, Mrs. Lewis J. Selznick, not to talk during the burn–which was expected to last about 45 minutes–because relative quiet would be needed to minimize confusion and bring all the carefully-rehearsed stunts off as planned. Menzies looked to Selznick to give the word to go, but the producer held off, awaiting the arrival of his brother, agent Myron Selznick. Not only did he want Myron to witness the start of the biggest production of his career, but he also wanted to meet his brother’s newest client, a 25 year-old actress who was, as Selznick later put it, “the Scarlett dark horse.” By eight o’clock, the temperature had dropped to 55 degrees and fog was starting to roll in. Menzies took his place on the platform, poised to conduct a conflagration of Wagnerian proportions, but Selznick held firm until Ray Klune advised him they wouldn’t be able to hold the extra fire and police personnel much longer. And so at 8:20, with his brother nowhere in sight, Selznick gave the OK to proceed.

As Menzies signaled Zavits, Stacey ordered the area cleared and the arcs brought up full, bathing the set in a light so brilliant it was startling. Zavits, from his perch behind a fire break, cued his men to start the flow of fuel to the pipes, while small fires were lit on asbestos tables in front of some of the lights, giving off trails of thick black smoke. As Wilbur Kurtz, technical advisor to the film, observed, “This smoke, streaming across the field of light, made the background leap in irregular and fast-moving patches of shadow–as if a blaze was in progress in back of the cameras.”

When the fuel was confirmed as spraying evenly through the nozzles and coating the wood as planned, Zavits activated a series of electric ignitions and the blaze erupted with a deafening whoosh. In moments the old sets were fully engulfed, the fire roaring up above the buildings and, as in the novel, throwing “street and houses into a glare of light brighter than day, casting monstrous shadows that twisted as wildly as torn sails flapping in a gale on a sinking ship.” To Linda Schiller, Selznick’s script secretary, “it was just suddenly the holocaust… it scared all of us… it was like a whole town suddenly going up in flames.”

Menzies waited for the effect to build as the crowd stood awestruck. Some recoiled from the intense heat and pervasive smell of gasoline, while others were strangely fascinated and transfixed by the scene. The flames were licking up into the sky as much as 200 feet when Menzies gave Zavits a cue to momentarily kill the fuel and start the water pumping. As clouds of white steam rose into the night air, he called for the powerful arcs gelled red and amber. The sky exploded in great masses of red and black–hot, violent colors–and with the fire returned to maximum intensity, the backdrop for Rhett and Scarlett’s escape from Atlanta was complete. The crews stationed at five of the six cameras began to roll film. Moments later, as stunt woman Donna Fargo, clad in Scarlett’s lavender mourning dress, took her position alongside Yakima Canutt in the wagon, Menzies leaned into the microphone and called, “Action!”

Fleeing Atlanta

The wagon carrying Rhett and Scarlett scurried into view from an alleyway off Peachtree Street, one of the Technicolor cameras catching a reverse angle of their gallop as they sped toward the fire. They rounded a burning shed, pulling boxes over as they went, and raced westward into the flaming yard. Exploding munitions turned them back and out toward the spectators as the wagon clambered over a section of track and cross-ties and got mired in the mud. Leaping down, Rhett tried to budge the horse, then, failing that, signaled Scarlett to hand over her shawl. Wrapping it around the horse’s head, Rhett was able to get the animal moving again, but then discovered their pathway blocked by still more fire. Forced back through a gap in the cars, they sped away as dust and smoke swirled furiously around them.

All the mad rearing and plunging were the work of a stunt driver lying prone on the floorboards of the wagon, peering through an opening between Scarlett’s legs and controlling the horse with wires running out to the bit. It was all Canutt, an accomplished stunt rider, could do to keep his face obscured from the camera and sustain the illusion he was in control of the thing. Fargo cringed effectively and hid her face, even as she surrendered her shawl. With the fire still raging, Menzies called for another run and the cameras changed positions. Quickly, Yak and his driver got back into the alleyway, again they emerged, and again they faced the wall of flame and veered off into the foreground. This time, on impact with the cross-ties, the left front wheel collapsed and the horse, in the chaos and the searing heat of it all, sat down. A gang of grips rushed onto the scene and cleared it for yet another run.

Around the corner, on the backside of the Kong set, Clarence Slifer, Jack Cosgrove’s assistant, was waiting with the high-speed camera to record the collapse of the giant wall at 72 frames-per-second–three times normal speed. But since Slifer had barely three minutes of film in the camera and couldn’t see what was happening on the other side of the wall, he and his crew had to watch a green light for their cue. And once rolling, there would be a very tight window of time during which a red light could tell them the structure was about to fall.

As the second wagon began its run, the fuel supply to the whole of the wall was brought up and, suddenly, it too was engulfed in flames. From his perspective, Slifer anxiously watched for his signal, but it failed to come as Menzies, momentarily distracted, was busy capturing the footage of the fire and the boiling smoke; angry flames to be optically added to foreground action in scenes later to be shot with the principals.

Meanwhile, the furious light cast on the low-hanging clouds drew scores of cars and thrill seekers, some eager to see what was happening, others convinced the entire neighborhood was going up. Switchboards lit up around the city as people wanted to know where the fire was. (Many thought M-G-M was burning, which handed Selznick a laugh.) With spectators and the noise of the surrounding traffic on the increase, Slifer finally got his cue. Rolling, he waited for the tractor to do its worst as exposed film ticked into the magazine at a ferocious pace. “When our counter reached 700 feet we were beside ourselves with fear that we would run out of film, as a magazine held approximately 950 feet of film.”

Seven-fifty, eight hundred, eight-fifty… there was less than twenty seconds of film left in the camera when the red bulb came on. The tractor lurched into motion and the skeletal remains of Skull Island, roughly 75 feet in height, came crashing down in a spectacular eruption of embers and debris. Moments later, the big blue camera was out of film, but the shot was there. As Slifer and his crew cleaned the movement and re-loaded for background plates, firemen with hoses on the periphery of the scene busied themselves shooting blazing fragments out of the night sky as if they were ducks.

With Rhett and Scarlett’s run and the wall’s collapse now safely in the can, the cameras again shifted positions, and two were re-loaded for the process of making background plates. A close-up was shot of Yak in the second wagon, passing a blazing line of fencing. Then the second double took a run past a burning boxcar, the camera trained to shoot through the open doors of the car, but the horse, having galloped into a confined space between the car and a wall of flames, balked at the containment and steadfastly refused to move.

With Rhett and Scarlett’s run and the wall’s collapse now safely in the can, the cameras again shifted positions, and two were re-loaded for the process of making background plates. A close-up was shot of Yak in the second wagon, passing a blazing line of fencing. Then the second double took a run past a burning boxcar, the camera trained to shoot through the open doors of the car, but the horse, having galloped into a confined space between the car and a wall of flames, balked at the containment and steadfastly refused to move.

As they gave up the shot, Selznick and Cukor suggested a close-up of some threatened explosives, but the fire was by now on the wane, and they decided they could get it later. It was just then that Myron Selznick, aglow from dinner and a steady flow of cocktails, rolled onto the property, accompanied by Laurence Olivier and his future wife, actress Vivien Leigh. David Selznick took his first look at Leigh in the flesh and knew instantly that she was Scarlett. “Later on, her tests, made under George Cukor’s brilliant direction, showed that she could act the part right down to the ground,” he said, “but I’ll never recover from that first look.”

The flames were methodically doused, and Menzies stood amid the ashes and the charred rubble of the set, water dripping from everything, the smell of gasoline still hanging in the air. Exhausted from the strain of it all, he lit yet another cigarette. Selznick came over to him, apologized for ever doubting that he could bring it off, and told him it was one of the greatest things he had ever seen. Nearly 12,000 feet of film had been exposed in less than an hour at a total cost of $26,319.55. As Selznick later wrote, “It was one of the biggest thrills I have had out of making pictures–first, because of the scene itself, and second, because of the frightening but exciting knowledge that Gone With the Wind was finally in work.”

(Reprinted with permission from James Curtis and Pantheon Books)

We urge you to purchase William Cameron Menzies: The Shape of Things to Come from your local book store. It is also available through our affiliate arrangement with Indiebound and Amazon.

James Curtis spent twenty-five years as a senior executive in the insurance and computer industries before turning full time to writing. He is currently researching what he hopes will be the definitive biography of Buster Keaton for Alfred A. Knopf. Simultaneously, he is completing a book about Mort Sahl to be released in conjunction with the groundbreaking satirist’s 90th birthday. His newest work, “William Cameron Menzies: The Shape of Films to Come,” was published in November by Pantheon. He is also the author of “Spencer Tracy: A Biography;” “W. C. Fields: A Biography” (winner of the 2004 Theatre Library Association Award, Special Jury Prize); “James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters;” and “Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges.” In addition, he has edited three books on film-related subjects, including a biography of actor Walter Huston. Born in Los Angeles, Curtis and his wife, Kim Geary, are longtime residents of Brea, California.

His website is here.

Turner Classic Movies featured an extensive Tribute to William Cameron Menzies recently. Some of the films come and go on their “Watch Live.”

Many of his movies are available from Amazon and your local video store (if you are lucky enough to have one near you). Clips and trailers are often found via a web search. Look at a list of his credits here.

On the set of Kings Row (1942), William Cameron Menzies shows how he visualizes a sequence with a continuity board. When the Breen Office cautioned the studio over this scene in which Drake (Ronald Reagan) discovers his legs have been amputated, Menzies threw the visual emphasis to Randy (Ann Sheridan) by reflecting in her anguished reaction shots the depth of Drake’s horror. (Photo courtesy of James Curtis)