Chapter 18: Majdanek

As much as I had not wanted to come to Poland at all, I really didn’t want to go to a Nazi concentration camp. I had had a bad experience with the Holocaust Museum in D.C., and that was with just displays of objects taken from camps. This prospect seemed more than scary; it was nauseating.

But for Jews visiting Poland, visiting a death camp had become obligatory. It was both a physical and emotional journey, providing a connection to their identity and to one another through the shared horror of the past. For some the camps were primarily evidence of the crimes, a memorial to those who perished, and an opportunity to remember. I felt obliged to visit Majdanek, but I was reluctant to do so because I feared its emotional power.

Majdanek is not as well-known to most people as Auschwitz and others, although it was the first camp to be liberated—by Soviet troops on July 23, 1944. Originally established as a forced labor camp, it became an extermination camp in the spring of 1942 when three camps built specifically to murder Jews (Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka) could not handle the large Jewish populations in southern Poland. The well-preserved gas chambers and ovens in the crematorium told part of the story.

Elizabeth holding her great-grandfather’s self-portrait at the Jewish Historical Institute in

Warsaw. Photo by Slawomir Grünberg

Self-Portrait 1931

It was written in some places that my great-grandfather was murdered at Treblinka. This was a guess based on a historical chronology of events and the fact that a preponderance of Jews were deported to Treblinka before the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April 1943. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website, of those who survived the uprising, “the Germans deported about 7,000 more Jews to Treblinka, and about 42,000 to concentration camps and forced-labor camps in the Lublin District. . . . Of this group, approximately, 18,000 Jews were sent to the Majdanek camp.”

I knew the odds my great-grandfather had survived the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and had been deported with the group of Jews sent to Majdanek would be slim in the absence of other evidence. But I knew from Perla and Grandpa George’s stories, and the timing of Perla’s escape from the ghetto, that Moshe’s survival until the uprising was pretty clear. And of those who survived the uprising, a substantial portion went to Majdanek. I also had another very important piece of evidence. Grandpa George’s memoir said Perla received a postcard from Moshe telling her he was well and hoped to paint at Majdanek.

Perla Rynecki was married to Moshe, 1929

I wrote to the Majdanek Museum before coming to Poland, both to request permission to film for the documentary and to ask if they knew anything about my great-grandfather. Permission to film was granted, but in regards to my great-grandfather, they knew nothing. Of course, records from the war were spotty at best, so that told me very little. It would have been nice to have independent confirmation, but as with so many things from the war, certainty was hard to come by. The best evidence I had suggested that Moshe died at Majdanek, so to Majdanek I went.

On Thursday, October 24, I woke to steady rain and a blustery wind. It was almost absurdly appropriate; I don’t think I could have imagined visiting a death camp on a beautiful sunny day. Cathy, Sławek, and I ate a quiet breakfast in the hotel. The stress of the trip had gotten to me; I felt sick—my throat hurt and my voice was hoarse. Cathy and Sławek both expressed concern and insisted I drink some hot tea. When we packed up for the day, I put on as many layers as I could—a wool hat, mittens, and my mother’s yellow rain jacket with the hood pulled up over my hat.

“Are you going to be warm enough?” Cathy asked, eyeing my attire.

“I hope so.”

“We should get an umbrella,” Sławek said.

“Maybe the hotel can loan us one,” Cathy said.

“I’ll ask,” I said, spying a few umbrellas in a stand by the front door.

Sławek opened the front door of the hotel and looked worried. With sheets of rain coming down and the wind whipping against the building, he was understandably concerned about his camera getting wet. I convinced the receptionist to loan me a small umbrella and tried to hold it over Sławek as we darted out the entryway and hailed a cab. We asked the driver to first stop at a drugstore, where Sławek consulted the pharmacist in Polish and then insisted I buy an abundance of cough drops and tissues.

The visitor center at Majdanek was a modern building with large glass windows overlooking the length of the camp. From inside the building I saw barbed wire fences, guard towers, fields of green, a few buildings, and two large monuments—an enormous, abstract stone sculpture at the camp’s entrance and a large mausoleum holding the ashes of the victims at the opposite end. I introduced myself to the man behind the desk. He told us which areas were off-limits to filming and asked us to be respectful of the site.

The Monument of Struggle and Martyrdom at the entrance to Majdanek is gargantuan; a wide, squat structure with two small pillars as a base, apparently struggling to resist the massive weight above. Its dark form was intended to evoke the gates of hell, but it struck me as equally about the crushing weight of memory. The sculpture was dedicated in September 1969, exactly thirty years after Germany’s invasion of Poland and less than two weeks after I was born. An abstract form on a hillside, its base was a gateway for visitors into the open fields and barracks below. I felt an almost irresistible desire to turn back, but I managed to keep my feet plodding forward.

- Photo by Sławomir Grünberg

Cathy tried to hold the umbrella over Sławek as we walked along one of the trails to a barracks off in the distance. But the wind picked up, and in a matter of moments the umbrella turned inside out. I stuck my hands deep into my raincoat pockets. Soon my fingertips lost feeling and my leather boots were soaked. My cold, wet feet, numb fingertips and toes, and the driving rain on my face only heightened the dread and helplessness I felt inside. I couldn’t imagine being in this environment, even during the “work camp” era of Majdanek, with inadequate clothing and food, to say nothing of backbreaking work and abusive guards. It was hard to imagine surviving a single day here, much less months or years.

The weather made my pilgrimage to Majdanek even more isolating and solitary, though I was with Sławek and Cathy. I walked, head bent forward against the wind and rain. I stopped between two guard towers to peer through the barbed wire fence and the downpour, toward buildings in the distance, outside the camp. I put my hand on the barbed portion of the fence, its sharp points threatening my fingertips. There was nothing particularly haunting or horrific about the scene in and of itself; the context I brought with me made it so. After a time, I let go of the barbed wire and turned toward Sławek. He said something which I couldn’t hear because the rain was so loud. Realizing I couldn’t understand, he gestured that he wanted to head toward the barracks, and I followed.

Photo by Sławomir Grünberg

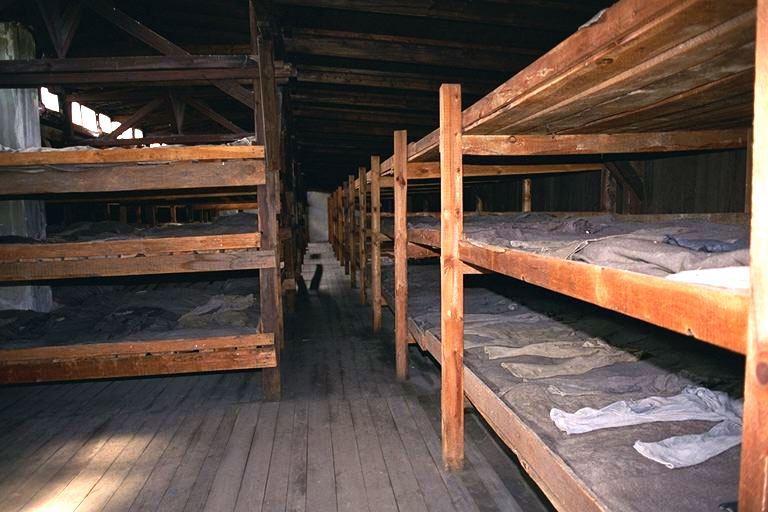

Once inside the small, plain wooden building, I appreciated the respite from the rain and wind. The building we stepped into had bunks—stacked wooden platforms, really. I knew from photographs I’d seen of prisoners held in other camps that the wood platforms were all prisoners had had to sleep on, and they shared these spaces with far too many others. There were no mattresses, no pillows, no down comforters or even threadbare blankets to keep them warm. There was no privacy, and little comfort save the presence of shared hardship. I pondered the stark living conditions and bleak prospects of the prisoners and then headed back out into the elements.

Photo © by Phillip Trauring, courtesy of A Teacher’s Guide to the Holocaust

It was hard to tell where I was going. Between the rain, wind, and my increasingly frozen feet, I focused on following Sławek. We went into another nondescript wooden building. It was dark inside, and it took me a while to figure out where I was. When I finally realized what I was looking at, I wanted to flee. Inside were rows of metal wire cages from floor to ceiling, filled with shoes. It was endless, the individuality of each shoe utterly lost in the monstrosity of what each represented. I tried to deny the nameless and faceless monument the shoes presented. I tried to find unique characteristics in shoes—to acknowledge and memorialize people rather than the mere numbers who were murdered. But it was impossible.

Photos courtesy of Majdanek State Museum

There was an easy exit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to escape when I felt overwhelmed. There was no easy way out at Majdanek. I came to know the horror of the Holocaust in a new and more personal way here. The buildings and preserved artifacts were an actual link to incomprehensible numbers of people, families and children, who had suffered and died here, in a nondescript bunch of buildings behind a barbed wire fence. I felt like I was reaching my breaking point, which was a problem, because though I could feel the death around me, this was the easy part. I hadn’t yet seen the crematorium.

Cathy, Sławek, and I went back outside. We looked toward the crematorium, which was near the other end of the camp. They weren’t ready for a walk in the rain either. We saw a sign for a museum—a heated space with a photographic exhibition about the camp. I felt a wave of guilt that I couldn’t handle the weather or my feelings. Clearly, the prisoners had never gotten a break. We went inside anyway.

It was warm in the museum, and I discovered that there was a bathroom with a hand dryer. I turned it on again and again, trying to defrost my fingers and my boots. I felt like I was cheating. Of course, getting sicker in some pale imitation of solidarity was also misguided, so I tried to take care of myself. In the museum’s historical exhibition and education center there were photographs, documents, stories, and information about the camp, guards, and prisoners. While the entire outside museum of Majdanek relied on knowledge the visitors brought with them, the inside space tried to commemorate victims, by showing preserved relics and documents associated with the camp. Camp officials had already told me they had no information about my great-grandfather. I looked anyway, hoping against hope for the unlikeliest of clues—sketches, signatures, anything that suggested my great-grandfather had been here—but I saw nothing.

After looking through the exhibits, we went to the shower rooms. For the first time in the camp, we were not alone; there were multiple groups of students from Israel there, many carrying the Israeli flag. A large number of them were seated on the floor, and group leaders spoke to them in Hebrew. I walked around them and moved farther into the building. I looked at the shower fixtures installed in the low ceiling and thought of how the Nazis had dispersed Zyklon B, which they used to murder so many. I wanted out. I wanted to leave right then. But there were no exit doors. To leave this space I had to, once again, walk through the middle of these large groups of students. I felt like I was trespassing in their space, though of course that was absurd. I was desperate for fresh air, torrential downpour and all.

“Can we leave now?” I asked Cathy.

“We need to go to the far end, to see the crematorium and mausoleum memorial.”

“Can’t we skip it?”

Cathy just looked at me. I knew she was right, though I wasn’t happy about it. I pulled the drawstrings of my hood tighter and tried to wiggle my toes. I couldn’t feel them at all.

“Let’s get this over with,” I said, and began the long trek down to the far end of the Majdanek complex.

Photo © by Rachelle M, Stone and Dust

The crematorium itself could be seen from far away—the brick chimney towered over the smaller wooden buildings it served. Inside, the crematorium was a row of four or five red brick ovens. The doors to the ovens on some were open and others were closed. There was a crowd here, and the teeming humanity felt oppressive. I looked at the front of the ovens and then walked around to the backside. I felt extremely nauseous. I had seen enough. I was more than ready to leave.

“We should film you here,” Sławek said.

“Is it really necessary?” I asked.

Sławek nodded.

“Cathy?” I asked.

Cathy nodded too.

I hated their answer, but I trusted Cathy and Sławek. I was too close to the moment, and it was emotionally too difficult for me to judge anything given my state of mind. We got the shot relatively quickly, and I was intensely relieved to be back out in the cold and rain a few minutes later.

(Photos © Elizabeth Rynecki unless otherwise noted.)

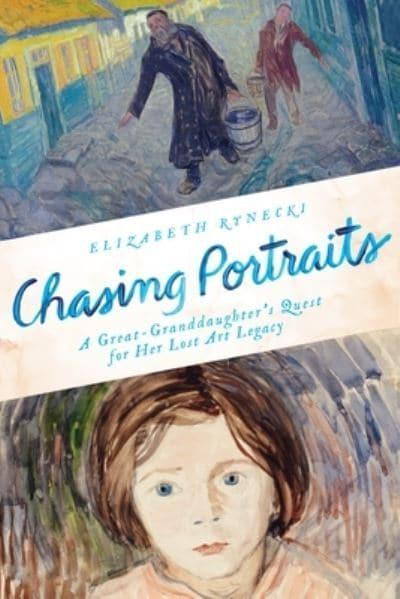

Visit the website for the book Chasing Portraits, published by Penguin Random House in September 2016.

E lizabeth Rynecki is the Director/Producer/Writer of CHASING PORTRAITS, her first film. She has a BA in Rhetoric from Bates College (’91) and an MA in Rhetoric and Communication from UC Davis (’94). Her Master’s thesis focused on children of Holocaust survivors. In 1999, Elizabeth designed the original Moshe Rynecki: Portrait of a Life in Art website. It is a virtual museum. Today, she continually updates it to keep it current regarding academic research, educational resources, and tracking lost Rynecki paintings.

lizabeth Rynecki is the Director/Producer/Writer of CHASING PORTRAITS, her first film. She has a BA in Rhetoric from Bates College (’91) and an MA in Rhetoric and Communication from UC Davis (’94). Her Master’s thesis focused on children of Holocaust survivors. In 1999, Elizabeth designed the original Moshe Rynecki: Portrait of a Life in Art website. It is a virtual museum. Today, she continually updates it to keep it current regarding academic research, educational resources, and tracking lost Rynecki paintings.

You can read Elizabeth’s story about making the film and see many beautiful paintings on EatDrinkFilms.

CHASING PORTRAITS has been on the film festival circuit for the past year, screening in Poland, Israel, and across the United States. The film had its NYC theatrical release April 26, 2019. It opens in Los Angeles at Laemmle Music Hall May 17th. Rynecki will be there for special filmmaker Q&As opening weekend. It will continue showing across the country.

The film’s official website features many paintings, events, a blog and more.

Moshe Rynecki: Portrait of a Life in Art website

Elizabeth’s grandfather, George J. Rynecki wrote Surviving Hitler in Poland: One Jew’s Story.

SOCIAL MEDIA WEBSITES Facebook Twitter Instagram

Elizabeth Rynecki reading from her book and speaking at the JCCSF in 2016:

An additional selection of paintings. “While Rynecki compulsively drew scenes of Jewish religious life, he also had a keen eye for exploring and visually narrating the daily rhythm of everyday life. Beyond the walls of the synagogue he dwelled on the unique qualities of ordinary lives – musicians playing to a crowd in the street, men kibitzing over a chess board, and women – women sewing, washing clothes, taking care of children, and working outside the home.” ER

Blowing Bubbles, 1931

The Water Carriers, 1930

Lathe Workers

Wedding dance, torn

Jewish Life In Poland The Art of Moshe Rynecki (1881-1943) is a collection of a few dozen of his paintings and is available as a printed book or ebook from the publisher or Kindle (ignore the book pricing on Amazon).

MOSHE RYNECKI (1881 – 1943)

Rynecki was born in Miedzyrecze, Poland, a small town east of Warsaw. Born into an Orthodox family, his love of painting was frowned upon by his parents, particularly his father. Despite his father’s efforts to dissuade his son from a life of painting, Moshe did draw and paint through much of his childhood while also attending to his regular studies at a traditional Yeshiva and then a Russian middle school. He eventually spent some time at the Warsaw Academy of Art (his dates of attendance are unknown). While he was in art school he met and married Paula Mittelsbach, the daughter of a Warsaw family of some means. While Moshe attended school, his wife was left to take care of their small art supply store on Krucza Street and their two small children (a girl and a boy).

Rynecki was born in Miedzyrecze, Poland, a small town east of Warsaw. Born into an Orthodox family, his love of painting was frowned upon by his parents, particularly his father. Despite his father’s efforts to dissuade his son from a life of painting, Moshe did draw and paint through much of his childhood while also attending to his regular studies at a traditional Yeshiva and then a Russian middle school. He eventually spent some time at the Warsaw Academy of Art (his dates of attendance are unknown). While he was in art school he met and married Paula Mittelsbach, the daughter of a Warsaw family of some means. While Moshe attended school, his wife was left to take care of their small art supply store on Krucza Street and their two small children (a girl and a boy).

Moshe’s most productive painting years were the 1920s and 1930s. During these years he primarily painted scenes of the Jewish community. His works show religious scenes (e.g., men studying the Talmud, Simhat Torah), images from everyday life (e.g. women doing household chores, men playing chess), and ultimately scenes from inside the Warsaw Ghetto.

In 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, Moshe realized his life’s work was at great risk of being destroyed. In an effort to protect and preserve his paintings, he bundled his collection of over 800 paintings and sculptures into a number of packages and distributed them to gentile friends in and around Warsaw. He told his family where the paintings were hidden so that after the war the family could collect the bundles and make the collection whole once again. He then willingly went into the Warsaw Ghetto to “be with my people and to document their lives.”

In 1943 Moshe was deported from the Ghetto. It is believed that he perished in the Majdanek concentration camp.