By Lincoln Spector

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY celebrated its 50th anniversary in style this year with two totally different restorations. Warner Brothers released new 70mm prints overseen by DUNKIRK and INTERSTELLAR director Christopher Nolan. Kubrick assistant Leon Vitali (himself the subject of a recent documentary) supervised a new, 4K digital restoration. The Castro Theatre in San Francisco offers the 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY 70MM/4K Challenge December 28-January 1 where you can see both versions.

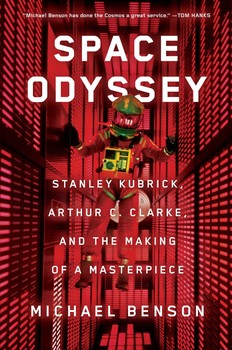

Simon and Schuster also published Michael Benson’s fascinating new book, Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece. It’s worth reading. Read an excerpt here.

More than almost any other cinematic masterpiece, 2001 cries out for a very special sort of theatrical presentation. The film was intended to be shown in Cinerama, which after 1962 meant 70mm film projected onto a very large, deeply-curved screen.

Cinerama Dome,Hollywood, 1993 by Hiroshi Sugimoto

(Listen to the film’s music in the original versions. Note that videos in this article also have sound. We suggest you read the article while listening to the music of your choice and return to watch the videos.)

Since June, 2018 I experienced the film in three very different theaters, and was reminded that not all 2001 presentations are equal. You need to know something about the film and the technologies of the time to understand why.

How it should be seen

By the time Kubrick and co-screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke started planning “the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction movie,” Cinerama was no longer the three-strip system of the 1950s. 2001 was shot on 65mm film, which has the same size frame as 70mm.

Kubrick and his collaborators kept Cinerama’s deeply-curved screen in mind as they made the film, creating an exceptionally immersive experience – especially for those sitting close to the screen.

By putting the people [or objects] on the sides close to the camera, and those in the center farther away, Kubrick matched the blocking with the curvature of the Cinerama screen

When the moon moves down in the opening titles, you feel yourself rising. The stargate (Beyond the Infinite) pushes you forward. Even static dialog scenes are blocked on a curve.

The Bay Area no longer has a Cinerama theater. Until this year, I hadn’t seen 2001 on a curved screen since 1975.

How it should be heard

In the 1960s, 70mm prints carried six magnetic, analog audio tracks – five front and one surround. The wide sound complimented the wide screen. When someone spoke on the far-left side of the screen, their voice came out of the far-left speaker. Today, almost all dialog comes out of the center speaker.

Courtesy of GraumansChinese.org

A SPACE ODYSSEY is no exception. When Bowman and Poole talk in the pod, their voices come from the left-center and right-center speakers.

When MGM rereleased the film on DVD in 1997, they created a more modern 5.1 digital mix – presumably with Kubrick’s blessing. That probably sounded better on a TV (especially a 4×3 TV), but it lost something on a giant screen.

The analog “unrestored” version

Christopher Nolan doesn’t like digital cinema. He loves physical film, and the bigger the format, the better. Consider his use of 70mm IMAX in THE DARK KNIGHT, INTERSTELLAR, and DUNKIRK.

Earlier this year, Nolan and Warner Brothers released “unrestored” 70mm prints of 2001 that claim to be the film as it looked in its original Cinerama release.

I’m skeptical. With analog film, image quality gets worse with each generation from the original camera negative. The 1968 prints were made directly from that negative. The new prints are three generations away: interpositive, internegative, and release print. And, as with any restoration, this “unrestoration” involved guesswork, requiring, according to the New York Times, “some imagining of what Kubrick would want, with prompting from the faded source material.”

Courtesy of Christopher Nolan and Variety

Nolan’s prints aren’t entirely analog. The audio is digital and has options for either the original six-track and the modern 5.1 soundtracks. A wise move: The six-track version is the original, but few theaters can play it.

The first two of my recent 2001 experiences came from Nolan’s “unrestored” 70mm prints.

The Castro Experience

For most movies, whether in 35mm, 70mm, or digital, the Castro is just about perfect. It can’t quite present 2001 properly, but it comes reasonably close.

I attended a 70mm screening of Nolan’s “unrestored” at the Castro in June. I sat in what I felt was the best seat in the house for this particular movie: front-row center. And sitting there, I fell in love with 2001 all over again.

I’m in no position to compare this with a 1968 print, but it looked very, very good. It looked grainier than I’d expect for the format it was shot and shown in, but I assumed that was from the multiple generations.

As much as I loved the movie, I knew that something was missing. The Castro has a very big screen, but not a huge one. What’s more, the screen is flat.

And then there’s the audio. The Castro cannot play six-track audio. So, I heard the film in the modern 5.1 mix.

The IMAX Experience

IMAX is the closest thing we have to Cinerama in the Bay Area. The frame is almost four times the size of standard 70mm. The screen is massively huge and slightly curved.

Warner Brothers made a handful of IMAX prints from Nolan’s version. In September, I saw one of those prints in the Metreon’s IMAX theater.

The IMAX screen isn’t as curved as Cinerama, but it’s curved enough to create something like Cinerama’s peripheral-vision experience. I felt myself moving in space (and no, I wasn’t on drugs).

At the Metreon, I sat fifth-row center. The first row in IMAX is too overwhelming even for me.

Another advantage: The IMAX theater used the original six-track sound mix, which emphasized the width of the image.

But it wasn’t a perfect experience. Something – I suspect it was dust on the film gate – wiggled on the screen. In dark scenes you could ignore it, but in bright scenes, it looked like insects scurrying on the walls.

Like most big roadshow films of the 1960s, 2001 starts with a musical overture, intended to be played while the curtain is sill closed. At the Metreon, unlike the Castro, this phenomenon had to be explained. A woman’s voice told us that the director wanted the film to start with music against a blank screen – not totally accurate, but close enough.

After the Intermission card faded away, a calm, male voice announced that the intermission will last about 15 minutes. Someone in the audience responded with “Thank you, HAL.”

The 4K digital restoration

The “unrestored” version isn’t the only new way to see 2001. Kubrick assistant Leon Vitali recently completed a 4K digital restoration for the home theater market. But it’s also available to movie theaters on DCP.

Vitali, the subject of the documentary FILMWORKER, worked closely with Kubrick. His job entailed checking the labs to make sure that prints looked exactly how Kubrick intended.

In early November, I finally got to see the digital restoration at the BAMPFA in Berkeley. Unfortunately, this is not an appropriate theater for 2001. The flat screen is too small, and because of the way the theater is designed, sitting in the front row can cause neck problems. I sat in the second row, with a wedge pillow and a neck pillow.

Going through BAMPFA’s 4K digital projector, the film looked beautiful. It was very sharp – except when it wasn’t supposed to be sharp. It looked at least as good as a new 70mm print. The images were rock steady – something that’s impossible with physical film.

Of course, many prefer film to digital projection. I take it on a case-by-case basis. For any particular motion picture, I go for the technology that looks the best – and very often, that’s digital.

But I can’t truly compare the analog and digital restorations of 2001. First, I saw them months apart. Second, how a film looks on a small screen can be very different than on a large one.

Take the 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY 70MM/4K CHALLENGE

We’ll get something close to a proper comparison as 2018 turns into 2019. EatDrinkFilms suggested this idea to the Castro Program Director Keith Arnold and he delivered. The film will be screened, alternating between 70mm and 4K DCP, at the Castro, Friday, December 28 through Tuesday, January 1. The program notes urge us to “choose your preference, compare, discuss! “

This comparison places the 70mm “unrestored” and earlier BluRay side-by-side. Based on the comments it is really a matter of individual taste.

I have now been to the Challenge and finally got a chance to compare the two new restorations of 2001: A SPACE ODYESSY on the same big screen. Through Tuesday, the Castro is alternating screenings of Christopher Nolan’s analog “unrestore” in 70mm and Leon Vitali’s digital restoration from a 4K DCP.

I watched the entire film digitally, but only the first half hour on film. This was my fourth 2001 screening in 2018, and I wasn’t ready for a fifth. Besides, I’d already seen Nolan’s version in 70mm at the Castro. As I did before, I sat front-row center.

Both versions were worthy of this great motion picture. But the 70mm print had problems unseen in the digital version.

The words in the opening credits vibrated enough to be noticeable – an inevitable problem on film but absent with digital projection. The bright, white walls of the space station also had a barely visible flicker. And yes, there were occasional scratches – a couple of them big. None of these showed up in Vitali’s restoration.

You can’t blame Nolan’s “unrestore” for those problems. The vibration and the flicker were there when Kubrick screened it on opening night. The scratches would have appeared sometime later. But those are inevitable problems with physical film.

But I have to assume that the color problems came from the unrestore. The colors were dull compared to the digital restoration. Worse, the African plains had a yellow cast that wasn’t on the digital version and, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t in the 1968 prints, either. A yellow cast generally suggests that the print was made from a fading negative. It’s the sort of problem that can only be properly repaired digitally.

I know the argument: “It was made to be shown on film and should always be shown on film.” I don’t buy it. Kubrick wanted his films to shown in the best possible way. Right now, for 2001, that means Leon Vitali’s digital restoration.

Read my BluRay comparison to 4K for home viewing review on BayFlicks.

Meet Michael Anders, longtime Castro projectionist as he prepares to show 2001 in 70mm.

Loved the movie; read the book

If you love 2001, you should read Michael Benson’s book, Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece. In a highly entertaining way, Benson explains how this masterpiece came about almost accidentally. Over a four-year chaotic process, no one was sure what the final movie would be like.

They were shooting the Discovery scenes while having no idea how the Dawn of Man sequence would work. Exposed negatives sat in a freezer for years before they could be taken out and exposed again for a special effect. Clarke struggled for years writing and rewriting a narration that was finally dropped. And after the premiere, MGM forced Kubrick to cut 19 minutes out of the film (Kubrick always insisted the cuts were his idea.)

They were shooting the Discovery scenes while having no idea how the Dawn of Man sequence would work. Exposed negatives sat in a freezer for years before they could be taken out and exposed again for a special effect. Clarke struggled for years writing and rewriting a narration that was finally dropped. And after the premiere, MGM forced Kubrick to cut 19 minutes out of the film (Kubrick always insisted the cuts were his idea.)

Benson respects Kubrick but doesn’t make him out as a one-man show. Clarke, Daniel Richter, Douglas Trumbull, and others made major contributions, and were cheated out of money, credits, and/or awards they deserved.

But Benson makes some bad mistakes. Five times he mentions the use of Panaflex cameras, which weren’t available until 1972.

You can read an excerpt from the book here.

2001: A Space Odyssey should be seen and seen properly. Let’s hope it’s available on the big screen for generations to come.

Lincoln Spector is a life-long cinephile and an award-winning journalist who writes about ent ertainment, culture, and technology. He’s also a frequent contributor to TechHive and Windows Secrets. His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Small Business Computing, Home Office Computing, Oakland City Magazine, Time Magazine, Technologizer, and InfoWorld.

ertainment, culture, and technology. He’s also a frequent contributor to TechHive and Windows Secrets. His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Small Business Computing, Home Office Computing, Oakland City Magazine, Time Magazine, Technologizer, and InfoWorld.

His local film blog, Bayflicks, contains a weekly newsletter covering speciality screenings throughout the Bay Area. His article comparing film and digital presentations (including Kubrick’s DR. STRANGELOVE) is a good companion to the above piece. We suggest that you sign up to receive his informative tips on movies to see —an invaluable service for film lovers.

A comparison of film formats. For explanations read here.

On its 50th Anniversary filmmakers discuss the impact 2001 had on them.

(Editor’s Notes: Thomas E. Brown writes about 2001‘s Pre- and Post-Premiere Edits and the various projection formats 2001’s Pre- and Post-Premiere Edits)

Dennis discusses his first time and recent screening with his daughter on Trailers From Hell.

Bill Hunt’s review of the new 4K BluRay discusses the differences and offers some background on the 4K from Warner Brothers’ Ned Price.)

Read more about 2001 on EatDrinkFilms and see rare ephemera, tributes, an insider setting the record straight, a letter to Kubrick and his response plus parodies.