Two biographies came out within a month of each other late last year about two very different comedians: Hope: Entertainer of the Century (Amazon or Indiebound) by Richard Zoglin and Becoming Richard Pryor (Amazon or Indiebound) by Scott Saul. These entertainers, generations apart, both had bumpy journeys “becoming” who we remember them to be. It was not all due to luck.

There’s a tendency in cinema biographies to focus on the mechanics of how certain performers created themselves in the public persona, how their influences shaped and expectations defined them. No popular entertainer is sui generis , certainly none who rise to prominence in periods of transition, when one media is being supplanted by another—when the accepted paths to fame are no longer easily available.

There’s a tendency in cinema biographies to focus on the mechanics of how certain performers created themselves in the public persona, how their influences shaped and expectations defined them. No popular entertainer is sui generis , certainly none who rise to prominence in periods of transition, when one media is being supplanted by another—when the accepted paths to fame are no longer easily available.

The book Becoming Mae West (1997, Amazon or Indiebound ) by Emily Leider was one of the first to foreground this approach, right there in the title tracing West’s career from stage to screen. The straightforward recounting of career highlights by such writers as Philip Norman or Todd McCarthy (sometimes seasoned with gossip, sometimes not) has made way for more insightful treatments along the lines of those by James Curtis and Shawn Levy, who position their subjects in the cultural context in which they developed and flourished, often within very specific (and admittedly lucky) circumstances.

Common ground between Pryor and Hope seems impossible to imagine, but Hope: Entertainer of the Century and Becoming Richard Pryor illustrate extended periods during which their subjects searched for a voice and a persona, a style of comedy and subject matter, risking failure before adopting surprisingly personal aspects of themselves to create an identity presented as a public face.

Zoglin traces the “construction” of Hope’s persona, created in a turbulent period of cultural transition when vaudeville was dying and movies started to talk. Bob Hope now seems hopelessly unhip compared to Pryor; he’s remembered for his endless Christmas specials entertaining the troops, surrounded with show business old-timers while lobbing softball political jokes. But he started on unsure footing, like his peers from the era in vaudeville, although half a generation later than those he competed with for radio time (Jack Benny, Fred Allen, Edgar Bergen). He hadn’t developed a comedic persona as an ethnic stereotype or through slapstick, two comedic modes already fading. Instead, he began to MC stage shows using a personalized style of anecdotes (“I was just backstage with the comic…”) and local references (“I hear you have a new bridge in town…”), which connected better with local audiences. He was often risqué on the radio, taking chances and charting more uncertain political territory, and in the process developed the art of the monologue, honing an everyman persona, commenting on any issue that happened to be in the news.

Zoglin traces the “construction” of Hope’s persona, created in a turbulent period of cultural transition when vaudeville was dying and movies started to talk. Bob Hope now seems hopelessly unhip compared to Pryor; he’s remembered for his endless Christmas specials entertaining the troops, surrounded with show business old-timers while lobbing softball political jokes. But he started on unsure footing, like his peers from the era in vaudeville, although half a generation later than those he competed with for radio time (Jack Benny, Fred Allen, Edgar Bergen). He hadn’t developed a comedic persona as an ethnic stereotype or through slapstick, two comedic modes already fading. Instead, he began to MC stage shows using a personalized style of anecdotes (“I was just backstage with the comic…”) and local references (“I hear you have a new bridge in town…”), which connected better with local audiences. He was often risqué on the radio, taking chances and charting more uncertain political territory, and in the process developed the art of the monologue, honing an everyman persona, commenting on any issue that happened to be in the news.

He started going overseas to entertain the troops in 1941 and hosted the Oscars a record 18 times, in the process becoming America’s MC. Hope is the precursor to Mort Sahl, Bill Cosby and Johnny Carson.

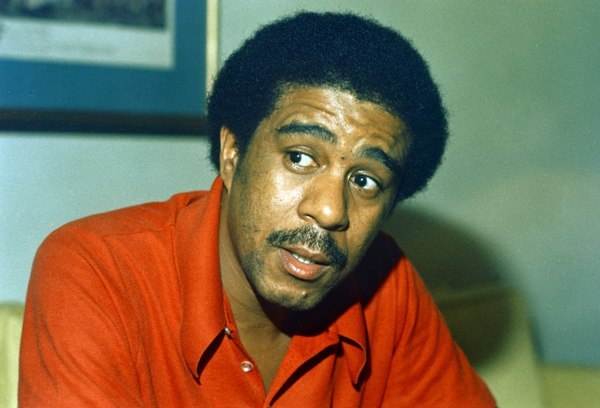

Saul’s Becoming Richard Pryor has a richer, certainly more colorful path to define. He traces Pryor from the earliest beginnings, his broken and sometimes dangerous home life in Peoria, Ill (locating newspaper clippings of crimes his father was accused of, and fleshing out details of the years he spent in his grandmother’s brothel). After starting his stand-up career as a Bill Cosby clone, Pryor began to introduce elements of the black experience and his own youth. He was increasingly uncomfortable reconciling what he was asked to do with what he really wanted: to perform more honest and controversial material at odds with what his bosses and his agents expected from a stand-up—material which challenged his ability to be booked on television and in mainstream clubs.

Saul’s Becoming Richard Pryor has a richer, certainly more colorful path to define. He traces Pryor from the earliest beginnings, his broken and sometimes dangerous home life in Peoria, Ill (locating newspaper clippings of crimes his father was accused of, and fleshing out details of the years he spent in his grandmother’s brothel). After starting his stand-up career as a Bill Cosby clone, Pryor began to introduce elements of the black experience and his own youth. He was increasingly uncomfortable reconciling what he was asked to do with what he really wanted: to perform more honest and controversial material at odds with what his bosses and his agents expected from a stand-up—material which challenged his ability to be booked on television and in mainstream clubs.

Pryor abandoned the conservative path to success (like George Carlin did at approximately the same time), walking out of gigs in Vegas and making his act more personal and sometimes almost surreal. He appeared at gigs without being announced, to ramble aimlessly and experimentally, a kind of self-destructive—and constructive?—jazz riffing. He also revealed an endearing vulnerability (and began to deploy the word “nigger” in his act to a degree that moved beyond shock impact).

Saul traces Pryor’s early influences and how his material developed. He’s not the only one to recently investigate the DNA of Pryor’s comedy: Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World That Made Him (Amazon or Indiebound) by David Henry and Joe Henry was published in 2013, digging the same ground. But Saul uncovers a previously-unknown trove of radio tapes from KPFA Pryor made in Berkeley in 1971, as well as film scripts, poetry, and other experimentations with various forms—a cache that demonstrates, Saul argues, Pryor’s unfettered creativity during the time, and his attempts to blaze new paths.

Bob Hope’s screen persona was in focus by 1938 (in The Big Broadcast of 1938 he sings a duet with Shirley Ross of “Thanks for the Memory,” which from that point on was tied to him as a theme song). They wrote him as a brash coward, quick with a wisecrack but avoiding physical confrontations, as well as a cheapskate and skirt chaser—all qualities the writers took from Hope himself. “He was playing, really, the real Bob Hope,” said Mel Shavelson.

The character was best realized in the “Road to …” movies with Bing Crosby. Hope never strayed from that successful persona; it made him appear vulnerable, as comfortable as an uncle. “Deep down inside, there is no Bob Hope,” observes writer Martin Ragaway in Zoglin’s book. “He’s been playing Bob Hope for so long that everything else had been burned out of him. The man has become his image.”

Zoglin traces Hope’s womanizing; his rising paydays; his acquisition of real estate; and how he refined the humor he was most adept at, surrounding himself with writers and performing before audiences most appreciative (overseas troops most in need, as well as the parents who wanted to glimpse their sons in the crowds). Hope never had a weekly television show, but his specials—sometimes as many as six a year—would get huge ratings.

Hope always considered himself a film actor who only occasionally did TV. But while he starred in more than 60 movies over 45 years, he’s remembered for his delivery—a relaxed and unthreatening conversational style.

Bob Hope was the role that best fit him. He amassed incredible power and leverage over NBC, and would walk through his shows, using cue cards and barely responding to his audiences. He was “Mt. Rushmore with cufflinks,” as described by Zoglin.

Pryor’s career never reached that mainstream ease. After the success of his early comedy records and film appearances, he attempted to create his own production company, hiring his friends. But he was unable to stop antagonizing those around him, which frustrated his pursuit of goals. Then there’s his tumultuous personal life, the troubled relationships with drugs and women so inexorably tied to his material. It’s an important parallel story to his career.

Pryor’s career never reached that mainstream ease. After the success of his early comedy records and film appearances, he attempted to create his own production company, hiring his friends. But he was unable to stop antagonizing those around him, which frustrated his pursuit of goals. Then there’s his tumultuous personal life, the troubled relationships with drugs and women so inexorably tied to his material. It’s an important parallel story to his career.

Both men are products of their time, and both used aspects of their own personalities to create an identity audiences were not expecting, but which they could connect with. Hope cast himself as a perennial loser, a coward and a wise-ass, never willing to engage with real danger, aloof and slightly put out (his ongoing jokes about never getting an Oscar are disingenuous—he received four honorary ones over the years). Pryor kept nothing off limits, revealing himself as equally vulnerable and anxious, his on-stage character fearful and furious, self-loathing and needy.

Saul’s story begins to wrap up around 1982, with the concert film Richard Pryor Live On The Sunset Strip. At that time Pryor is at the critical height of his powers, while also having accidentally set himself on fire. For Saul’s purposes, he’s finished “becoming” who he needed to be.

Saul’s story begins to wrap up around 1982, with the concert film Richard Pryor Live On The Sunset Strip. At that time Pryor is at the critical height of his powers, while also having accidentally set himself on fire. For Saul’s purposes, he’s finished “becoming” who he needed to be.

Pryor’s about to “unbecome,” with the odd and disappointing The Toy (1982) and Brewster’s Millions (1985) looming in the near future. In no more than 10 of Pryor’s 35 film appearances might he be considered the true star. He more often guest-starred (1972’s Lady Sings The Blues , 1976’s Car Wash , 1983’s Superman III ) or co-starred (three films with Gene Wilder; 1978’s Blue Collar ). Hollywood didn’t know what to do with him and he bounced from historical recreations (1976’s Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings , 1977’s Greased Lighting ) to well-meaning but toothless Hollywood comedies (1982’s Some Kind of Hero ).

His legacy resides in the three concert films, 1979’s Live In Concert , and 1982’s Sunset Strip and Here and Now, where he could most be himself.

Zoglin covers Hope’s later years on the wrong side of the youth movement, when he supported Nixon and the war in Vietnam and exhibited a stubborn unwillingness to retire or change his shtick. He did not age gracefully. It’s clear in Saul’s book that Pryor’s journey was unfinished—he never found an equilibrium the way Hope did, but he also never became irrelevant. His passing in 2005 at the age 65 robbed us of a sense of closure.

Saul isn’t interested in Pryor’s decline and death from MS. The book isn’t incomplete, Pryor’s life is.

Hope died in 2003 at age 100, only two years before Pryor. Their orbits crossed only one time—both appeared in 1979’s The Muppet Movie , although not together.

Zoglin and Saul present their subjects as keenly aware of public identity. Each analyzed his own strengths, deconstructed himself, and built a career that led to new ways of saying things and looking at the world. Both Hope and Pryor fought their way to success, ignoring common wisdom, while looking inward to individual characteristics and stubbornly holding onto a vision of self. They both changed comedy forever.

To read an excerpt of Hope: Entertainer of the Century, click here.

To read an excerpt of Hope: Entertainer of the Century, click here.

Roger Leatherwood worked in all levels of show business over the last 20 years, from managing the world-famous Grand Lake Theatre in Oakland to projecting midnight movies to directing a feature about a killer, Usher (2004), that won numerous awards on the independent festival circuit. He currently works at UCLA managing the instructional media collections, which is its own kind of show business. His film writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Bright Lights Film Journal, European Trash Cinema magazine, and his mondo-cine.blogspot.com. His review of Shawn Levy’s Robert De Niro: A Life (Amazon or Indiebound) appeared in EatDrinkFilms issue 39.

Roger Leatherwood worked in all levels of show business over the last 20 years, from managing the world-famous Grand Lake Theatre in Oakland to projecting midnight movies to directing a feature about a killer, Usher (2004), that won numerous awards on the independent festival circuit. He currently works at UCLA managing the instructional media collections, which is its own kind of show business. His film writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Bright Lights Film Journal, European Trash Cinema magazine, and his mondo-cine.blogspot.com. His review of Shawn Levy’s Robert De Niro: A Life (Amazon or Indiebound) appeared in EatDrinkFilms issue 39.