Robert De Niro is an enigma in the canon of American actors, nailing in just three years of the first decade of his screen-acting career such explosive and indelible performances as Johnny Boy in Mean Streets (1973), the young Vito Corleone/Marlon Brando in The Godfather Part II (1974), and Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976). This amazing early stretch of his career culminated in his triumphant portrayal of Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull (1980).

Soon thereafter he began playing quieter, more introspective characters, in smaller roles within less important films; for example, choosing the meek photographer in Mad Dog and Glory (1993) over the gangster role, ultimately played by—wait for it—Bill Murray (no wonder you haven’t heard of it) or assaying serviceable but unremarkable support in films such as Backdraft (1991) and Jackie Brown (1997). There were occasional odd, nearly-mad blips—the creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) comes to mind—but 10 years after playing Al Capone in The Untouchables (1987) he was making outright fun of his old screen persona by playing comedic gangster/tough guys in the two Analyze This (1999, 2002) and three Meet the Parents (2000, 2004, 2010) films. Ironically, this artistic slump yielded the biggest grosses of his entire career, for a new audience who hadn’t even heard of Travis Bickle.

Soon thereafter he began playing quieter, more introspective characters, in smaller roles within less important films; for example, choosing the meek photographer in Mad Dog and Glory (1993) over the gangster role, ultimately played by—wait for it—Bill Murray (no wonder you haven’t heard of it) or assaying serviceable but unremarkable support in films such as Backdraft (1991) and Jackie Brown (1997). There were occasional odd, nearly-mad blips—the creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) comes to mind—but 10 years after playing Al Capone in The Untouchables (1987) he was making outright fun of his old screen persona by playing comedic gangster/tough guys in the two Analyze This (1999, 2002) and three Meet the Parents (2000, 2004, 2010) films. Ironically, this artistic slump yielded the biggest grosses of his entire career, for a new audience who hadn’t even heard of Travis Bickle.

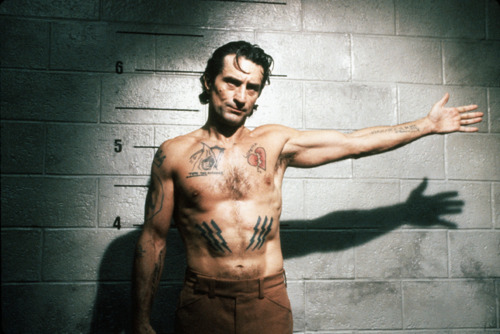

Is every great artist who burns so bright and so honestly doomed to disappoint us? (Brando and Stella Adler’s Method acting studio seem the lynchpin to De Niro’s acting, as well as the close study of his painter father’s bohemian, eccentric, almost obsessively self-destructive life choices.) De Niro’s choices became less interesting and more forgettable. For every shot of pure adrenaline such as his Max Cady in Cape Fear (1991) there was a Fearless Leader in The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (2000).

What happened? Is this trajectory different from that of any other method actor? After all, late in his career, Brando played Superman’s dad, and sent up his own mobster persona in The Freshman (1990).

This is the puzzle Shawn Levy teases out over 600 pages in De Niro: A Life, tracking the actor’s life with little material beyond his films. De Niro’s always been a notoriously reluctant interview subject, seldom doing extensive publicity, and he can be inarticulate to the point of autism when talking about his craft. His interviews sometimes read like Beat poetry (“Well … It’s complicated … Getting into it … It’s a personal thing … Is that okay?”). He’s attempted to hide his offscreen life as much as possible. It includes a family, kids, growing real estate and restaurant empires and charity concerns, but also, invariably, involvements with scandals (including a late night visit to John Belushi’s bungalow the night before his death), womanizing, a palimony suit, and legal scrapes with paparazzi.

De Niro: A Life draws from writing—mostly high profile—by critics, and observations from colleagues who’ve marveled at De Niro’s obsessive level of preparation and attention to the details of his roles. Critically, Levy also had access to De Niro’s papers and shooting scripts and the copious notes he made on them. He quotes from them extensively, building a picture of a serious working actor in much the same way De Niro built his characterizations. Levy reveals De Niro’s thoughts and process—the result is a mini Actors Studio class that spotlights what he’s thinking when he’s researching and filling in a character, tic by tic, mannerism by mannerism, cufflink by cufflink.

De Niro: A Life draws from writing—mostly high profile—by critics, and observations from colleagues who’ve marveled at De Niro’s obsessive level of preparation and attention to the details of his roles. Critically, Levy also had access to De Niro’s papers and shooting scripts and the copious notes he made on them. He quotes from them extensively, building a picture of a serious working actor in much the same way De Niro built his characterizations. Levy reveals De Niro’s thoughts and process—the result is a mini Actors Studio class that spotlights what he’s thinking when he’s researching and filling in a character, tic by tic, mannerism by mannerism, cufflink by cufflink.

Does the work reveal the man? Are the limbs he chooses to go out on as interesting as the ones he doesn’t? As Adler says in a quote repeated more than once, “Your talent is in your choice.”

Levy peppers in biographical data (and there’s much more in the public record than you realize) as he proceeds chronologically through De Niro’s career, covering each film. He fully investigates De Niro’s life, and with a minimum of prurient detail considering how much he uncovers—how the turns in De Niro’s personal fortunes informed and confounded his choices, giving a natural flow to what might seem a chaotic career.

While Levy includes references to drug use and De Niro’s romantic preference for black women, he’s never one to focus on the unsavory or salacious. The level of research and context is the same in his Jerry Lewis biography, King of Comedy (1997) which turns what easily could have been a one-note personality portrait into a mini-history of 20th century entertainment, from vaudeville and the Borsch Belt, to nightclubs to movies and television. Ready, Steady, Go! (2003), his survey of Swinging London in the ‘60s, is equally rich and balanced. Here, too, his writing is generous and rigorous. And—rare in star bios— he writes critically about De Niro’s triumphs as well as the disappointments.

Inevitably, the chronological examination of De Niro’s life begins to disappoint, as the actor’s “groove becomes a rut,” and the bravado and risk-taking of Raging Bull and The Mission (1986) are overtaken by more reserved and un-showy performances in A Bronx Tale (1993) and Casino (1995), then devolve the odd tragedy of his roles in Showtime (2002) through Last Vegas (2013). The fading promise of the greatest method actor of our generation, fully documented here on the twin tracks of his professional and private life, can’t quite be explained or justified.

But perhaps Levy conveys that the method is the madness, and its dedication to truth—wearing clothes from Al Capone’s tailor in The Untouchables ; learning to drive a vintage ‘60s bus for A Bronx Tale—approaches a point of purity. Raging Bull , arguably De Niro’s crowning performance, ends pointedly with LaMotta looking in the mirror practicing Brando’s monolog from On The Waterfront (1954) for his nightclub act: a famous method actor playing a broken-down boxer playing another famous method actor playing another broken-down boxer.

Ray Liotta, Robert De Niro, Paul Sorvino, Martin Scorsese and Joe Pesci in publicity still for Goodfellas .

The hall of mirrors is so twisted and self-referential one could get lost in it, but De Niro and Scorsese make the moment so painful, so personal and so specific that it says more about the character than 1000 words of exposition. And that choice—credited to De Niro—may say more about the actor than Levy’s 600 pages.

Come back next week as EatDrinkFilms shares an excerpt from De Niro: A Life in issue 40.

We encourage you to shop at your local bookstore, but you may also find books and videos about Robert De Niro at our affiliates: Indiebound and Amazon.

Roger Leatherwood worked in all levels of show business over the last

Roger Leatherwood worked in all levels of show business over the last

20 years, from managing the world-famous Grand Lake Theatre in Oakland to projecting midnight movies to directing a feature about a killer Usher (2004) that won numerous awards on the independent festival circuit. He currently works at UCLA managing the instructional media collections, which is its own kind of show business. His film writing has appeared in numerous publications including Bright Lights Film Journal,

European Trash Cinema magazine, and his mondo-cine.blogspot.com.