by Frako Loden

[Be warned: Plot spoilers abound]

Mizoguchi Kenji (1898-1956) is always in the holy trinity of directors—Kurosawa Akira and Ozu Yasujirô are the other two—invoked by Western cineastes as Japan’s greatest. But perhaps aside from his 1953 Ugetsu , which won a Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, few non-scholarly filmgoers have actually seen his films. Starting this week, Bay Area filmgoers will get a chance to view 16 of Mizoguchi’s most frequently screened works during the series “A Cinema of Totality” at UC Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive (July 19–Aug. 29, 2014), all on 35mm film.

It’s not just his signature gliding camera that defined Mizoguchi. He glided as gracefully from studio to studio as he did from one literary form to another, making adaptations of works by classical storytellers Ueda Akinari and Ihara Saikaku as well as near-contemporary novelists Izumi Kyôka and Mori Ôgai; puppet-theatre and kabuki plays and historical epics. Although he worked at several studios, predominantly Nikkatsu, Shochiku, Daiei and a number of independent studios in between, he enjoyed long-term collaborations with screenwriter Yoda Yoshikata and cinematographers Miki Minoru and Miyagawa Kazuo. He helped make the careers of several legendary Japanese actresses such as Irie Takako, Yamada Isuzu, Tanaka Kinuyo and Kyô Machiko. He made over 80 films until his death at the relatively young age of 58.

Mizoguchi’s dominant theme—the second-class status of women—was a reality in his own life but started as a commercial decision made for him by Nikkatsu studio heads who thought other directors were making enough male-centered films. Mizo witnessed women’s woes firsthand and profited from them. After his elder sister was sold off to a geisha house, a rich patron later married her, enabling her to support the entire Mizoguchi family and find jobs for Kenji that led to his movie career. He lived off her and other women, surviving one jealous stabbing by a house-call hooker and abandoning more than one to prostitution. He was tortured by the possibility, despite evidence to the contrary, that he had infected his wife with syphilis that led to her mental breakdown.

Japanese critics called Mizoguchi a “feminisuto,” something almost opposite to our meaning of the word feminist. A feminisuto is a man who adores and worships women but doesn’t necessarily think they deserve equal rights with men. A woman’s suffering becomes an aesthetic object, not cause for preaching or polemic. There is, however, plenty of anger—expressed almost shockingly in Osaka Elegy (1936), as geisha Omocha, who’s been tossed from a moving car and now lies in a hospital, cries, “No matter how much we do for men, they abandon us when it suits them. If we do our jobs well, they call us immoral. …Why do we have to suffer like this?” I’m sure Mizoguchi’s actresses saw the irony in having to repeat these lines in take after take to please their tyrannical director.

In his postwar research visits to Yoshiwara, the centuries-old red-light district of Japan then populated by pam-pam girls, or prostitutes catering to US Occupation soldiers, he told the startled women, “Men are the reason you’re here. They’re responsible. I’m responsible.” His most deeply felt films show all the ways women suffer without destroying their innermost spirit.

That doesn’t mean Mizoguchi’s women are hapless victims. His most memorable scenes show them seducing men in a winsome, innocent way. The director’s celebrated mobile camera plays along by backing up to let the women take those steps and then settles at a slightly high angle, like a cat atop a bureau, to watch them make the final gesture. Sometimes it’s a smile hidden behind a sleeve, an overwhelmed faint, or an embrace that knocks them both down and seals their fate.

Inevitably my favorite Mizoguchis are the ones I’ve seen the most often (courtesy of Janus / Criterion), and these fall into that phase of his career when his films amazed Westerners, primarily the proto-French New Wave critics and filmmakers, and won Silver and Golden Lions at the Venice Film Festival. The first was The Life of Oharu (1952), which after repeated viewings I’ve decided is not as miserabilist as I once thought. Sure the film version doesn’t give its heroine the benefit of a vital sexuality that she has in its literary forebear, Saikaku’s 1686 tale The Life of an Amorous Woman, which resembled Moll Flanders in celebrating a woman’s erotic life. But she does hold her head high as she goes from being a court lady to a lord’s concubine to a Shimabara courtesan to a merchant couple’s hairdresser to a fanmaker’s wife to a nun-in-training to a thief’s companion to a common prostitute, and finally a beggar nun. It’s amazing that actress Tanaka Kinuyo is believable in all these sub-roles over the 30-year storyline.

Oharu has her moments of fighting back, even if the outcome is futile. As a hairdresser, she incurs the jealousy of her mistress and has her hair cut. Oharu gets her revenge by training a cat to claw off the mistress’s hairpiece when she’s in bed with her husband, revealing her bald head to his horror. At the end of her road as an elderly streetwalker, Oharu is tricked into being displayed to pilgrims as an old witch, the embodiment of “every sin and misery known to man.” Enduring their revolted stares and pocketing her money, Oharu can’t resist acting the part of a real witch by hissing and unsheathing her cat-claws to them, frightening them.

Mizoguchi’s heroines are in constant struggle against the social edifices they’re trapped in. Even if an institution like the geisha remains constant, its practitioners differ even within a generation. In Sisters of the Gion (1936), Umekichi is docile while her younger sibling Omocha is a moga, short for “modern girl” and the Taishô-era (1912-1926) equivalent of the American flapper. The moga wore Western dress instead of the kimono and bluntly expressed her right to economic and sexual independence. Omocha is not too shy to be seen by Umekichi’s patron in her underwear, casually brushing her teeth. And when he leaves she scolds her compliant sister: “Men come here and pay money to make playthings out of us. …If that’s how men are, it’s only fair to find a patron and take him for all he’s worth. Otherwise, you lose.” In A Geisha (1953), the mentor Miyoharu is traditionally yielding and the trainee Eiko is frank and sometimes even sarcastic with her gestures. Sloppy drunk at her debut, Eiko calls Miyoharu “avant-guerre” for being too old-school submissive. Both the younger prostitutes Mickey and Yasumi of Street of Shame (1956) don’t suffer pangs of conscience if fleecing their clients brings them financial independence.

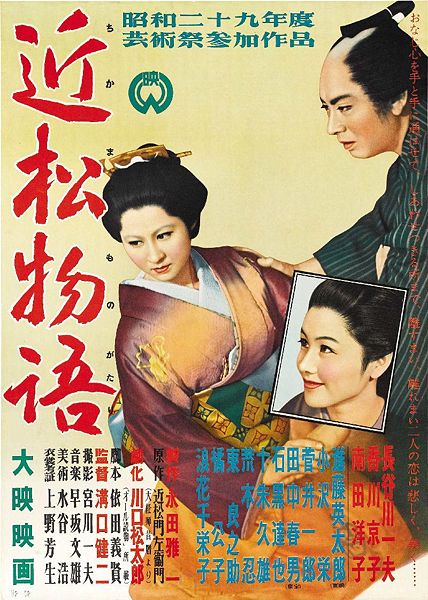

Love is the force that drives a woman to sacrifice herself but also to live. In a powerful scene from Crucified Lovers: A Story from Chikamatsu (1954), Osan the printer’s wife and Mohei his top apprentice, not yet lovers and facing unfounded criminal charges, plan to commit suicide from a boat. But when Mohei confesses his secret love to her as he prepares her for drowning, she stands up in the boat and decides she wants to live. Her sudden passion, boiling over now that her social status is in ruins, brings life back to her. A sprained ankle doesn’t stop her from chasing him down when he tries to abandon her for her own sake. Her insistence that they live is the misstep that leads to their final fates.

Scholars see high and low angles in Mizoguchi’s films as indicating hierarchy not just in social class but in romantic love. The idealized posture of lovers, seen in Cascading White Threads (not screening in this series), The Life of Oharu and Ugetsu (1953) , is of the lower-status man looking up at the higher-status woman, ennobled by love. But love, no matter how true, is no match for this social difference and will always end in tragedy.

A low-angle shot watches the proud and happy, if unequal, lovers from Chikamatsu’s tragedy, lashed together on a horse, as they’re carried to their execution. But the crane shot has the last say as in so many Mizoguchi films, ascending to look down on a street full of onlookers as the horse carries the lovers away from us in an ironic wedding / death march, where they are finally equal. This signature concluding crane shot can be seen at the end of Mizoguchi’s most famous films, Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff .

Like in so many Japanese folktales and stories, Mizoguchi’s women, especially mothers, gain power by their absence or death, such power manifesting in their disembodied voices. My first encounter with Sansho the Bailiff (1954) was not the film itself but the writings of French film theorist Michel Chion, who showed how the beckoning song of the children’s banished mother gives strength to the self-sacrificing daughter and guidance to the son who is finally reunited with her. We see a similar binding strength in the voice of the murdered Miyagi in Ugetsu , who seems to hold her family together with her gentle voice from the grave. Both women are played by Tanaka Kinuyo, Mizoguchi’s muse and possible unrequited love of his life and the icon of eternal womanhood for many other filmmakers. (Her films enjoyed a complete retrospective in Tokyo in 2009.) She’s also the rare Japanese actress to have directed her own films, six altogether starting in 1953 (the year she appeared in Ugetsu ). Their brilliant partnership of 15 films fell apart when he evidently interfered with her being hired as a director by Nikkatsu.

Mizoguchi’s gliding camera movements evoke the earthbound as well as the ethereal. Sisters of the Gion (1936)’s opening credits over a mambo soundtrack give way to a remarkable tracking shot through a house cluttered with furniture being auctioned off as the bankrupt merchant couple bicker in the back rooms. Nearly 20 years later, Ugetsu ‘s most celebrated traveling shots occur after Genjûrô is seduced by the Lady Wakasa. The camera glides magically from their wedding bed to the hot spring, then to a vast lawn by a shimmering lake where the lovers picnic in unimaginable pleasure.

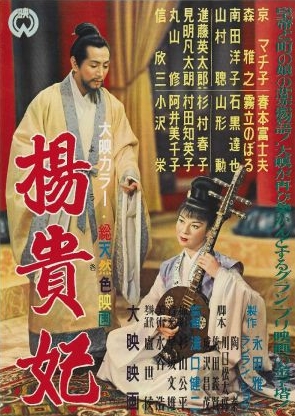

Mizoguchi’s final films tended toward the phantasmagoric. The 1955 Princess Yang Kwei-Fei , a color Daiei co-production with Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers, evokes a bizarre not-quite-Japanese, not-quite-Chinese—maybe Sternbergian Orientalist is the best way to describe it—8th-century imperial court through which Kyô Machiko’s sleepy-eyed concubine glides to her eventual tryst with the executioner’s noose. The same actress sports a ponytail and capris and leaps into a plastic clamshell to pronounce herself Venus in the 1956 Street of Shame . She even cynically offers herself to her wealthy father. The prostitutes’ varied styles of coping clash almost as wildly as the music does with its milieu—Mayuzumi Toshirô’s soundtrack is a surreal, spaced-out symphony of musical saw, women’s chorus and plucked strings.

Street of Shame , released as the latest anti-prostitution legislation was being dickered over, shows that the profession is a constant no matter what governments legislate, but that some women know how to game the system and its vulnerable men—its feminisutos—to set themselves up for life. Within five months of the film’s release, Mizoguchi was dead from leukemia. His life and peerless filmmaking career glided through the most tumultuous half-century of Japanese history and social convulsions.

Postscript: Many of the Mizoguchis have not been seen at Pacific Film Archive since a larger Mizoguchi retrospective from 1996. A few have screened in 21st-century series such as “Taisho Chic,” “Nikkatsu at 100,” “Japanese Divas” and the 50th anniversary (2006) of the director’s death. We won’t be able to see as many here as the Harvard Film Archive retrospective of all 30 extant films that will finish screening this month. I’ll particularly miss The Famous Sword Bijomaru (1945) and The Love of Sumako the Actress (1947), which I won’t be able to travel to the East Coast to see.

Frako Loden is a free-lance film writer who contributes to Documentary.org and Fandor. She teaches film history and ethnic studies at California State University East Bay and Diablo Valley College. She doesn’t like anyone messing with her assigned seat at the Pacific Film Archive.

NIce appreciation, Frako! I especially like your comparison of his camera to a cat.

Thanks, Larry!