By Louise Dunlap

My first reaction is “No way I’m going to review a film with the name “R——.“ I’ve spent too long telling relatives in the nation’s capital how their team’s name evokes bloody skins of the First People of our continent hunted for bounty. Even though this film acknowledges the R-word as a slur, even though today’s reviewers think it progressive for its time, I’m reluctant. Our history is one white person’s version of Indians after another—with Hollywood in the lead. I don’t want to join the thread.

But then I look at the specs.

This silent film was made 90 years ago in 1929, the year my father was a college freshman, forming ideas to pass down to me. It could take me to the heart of what a Buddhist teacher calls America’s Racial Karma—an awesome trip into past layers of our collective consciousness and what I hope is our emergence from racism. What were white folks thinking in 1929 when this film was made, and had we begun to realize how our history is grounded in genocide? I decided to take a look at the film called “R——“ being shown at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival December 7th, with live musical accompaniment by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. And I recommend it for white Americans seeking to decolonize—along with a few companion films and other resources to help you catch what’s missing in this dramatic and visually beautiful film.

The plot centers on Diné (Navajo) and Pueblo communities said to be in perpetual enmity, whose children are taken from their families to a government boarding school for assimilation—to have their minds colonized.

In such a school, Corn Flower (Pueblo) becomes the only friend of Wing Foot (Diné), who becomes a track star at all-white Thorpe College. (Could the name be a nod to the legendary Native Olympian Jim Thorpe?) Wing Foot wins on the field but is taunted and reviled as a “R——” in social spaces. Returning home in an elegant suit and tie he must navigate two cultures and reunite with Corn Blossom against impossible odds.

In such a school, Corn Flower (Pueblo) becomes the only friend of Wing Foot (Diné), who becomes a track star at all-white Thorpe College. (Could the name be a nod to the legendary Native Olympian Jim Thorpe?) Wing Foot wins on the field but is taunted and reviled as a “R——” in social spaces. Returning home in an elegant suit and tie he must navigate two cultures and reunite with Corn Blossom against impossible odds.

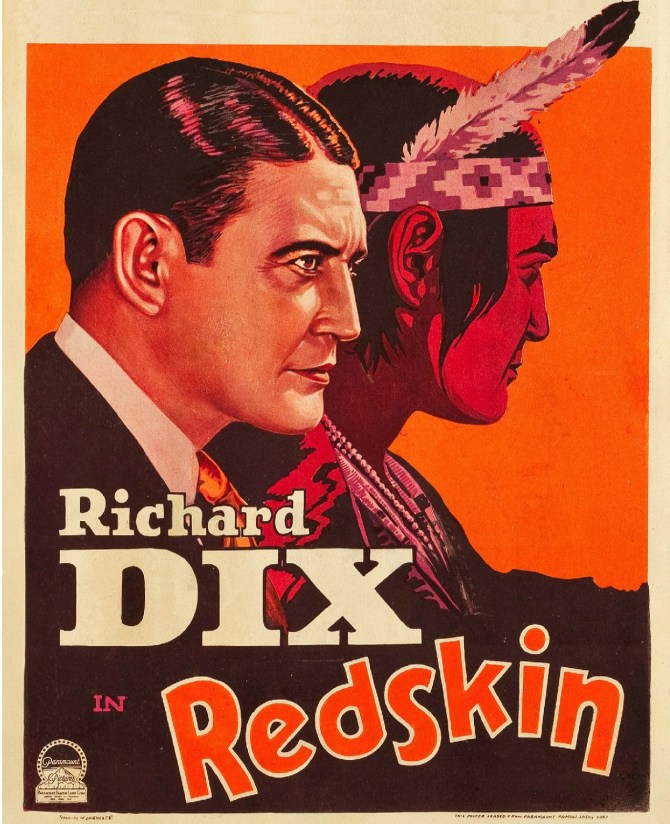

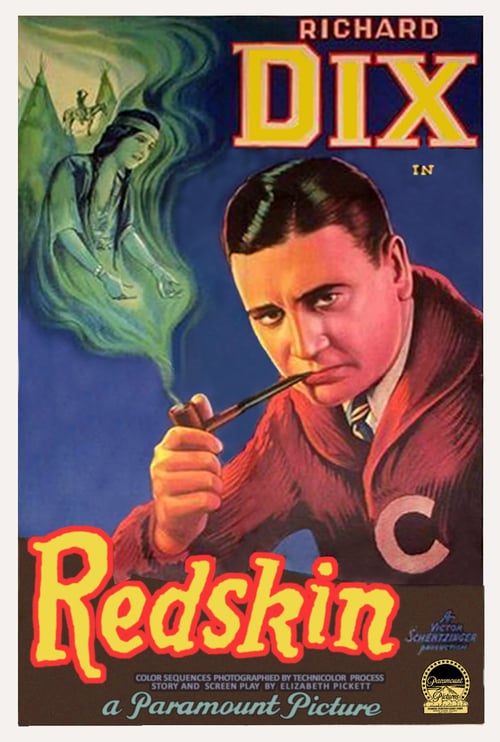

You’ll notice right away that there are no Native actors in this film. Wing Foot is played by Richard Dix, who also starred in THE VANISHING AMERICAN (1925), based on a Zane Grey novel about the “plight” of Indians. (Dix looks uncannily like photos of my own young father who was also an athlete and a scholar and considered handsome.)

Even the “Indians” who dance and play drums in the Pueblo and Diné scenes have non-Native faces. You’ll see how they are portrayed as mostly dirty and lackluster. Wing Foot himself thinks his people are superstitious and steeped in “witchcraft,” missing the benefits of civilized life—which he plans to change. You’ll see, when the dramatic ending rolls around, that oil and the extractive industry, which has so devastated the Navajo Nation, play an unchallenged role in his plan. “Keep it in the ground!” has not become a mantra. You’ll see that settler-colonial values of personal ownership infect both Diné and Pueblo in the film, though a careful study by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz shows that this was not the case. You’ll notice very early in the film that both white and Native men call the women “mine.” Small wonder 21st century Diné teacher Pat McCabe (Woman Stands Shining) has made it her lifework to restore the balance between masculine and feminine destroyed by colonialism. I have heard her speak of this project and of how she herself was harmed by being sent away to school.

To put this film in context, it’s important to understand the magnitude of the boarding school problem in Native life today. “R——“ shows us just a little of the harm it caused—Wing Foot’s forced abduction from his Diné home and the whipping he is given for refusing to salute the American flag. The film shows lasting scars for this one child, but doesn’t touch on the systemic nature of the trauma—how generations of children all across the continent were traumatized by an assimilation policy designed to “kill the Indian, save the man.” You can learn the full truth in a beautiful Native-made documentary THE WELLBRIETY JOURNEY TO FORGIVENESS that is offered freely on YouTube (see below) to assist in healing. In it are the real stories of far more brutal beatings, sexual abuse, language loss, shaming, and lasting harm to families—deeply touching stories the tellers were sharing for the first time. You’ll learn how forced separation of children from parents is explicitly part of what the UN would later identify as genocide. In our times, a massive movement to heal from boarding school trauma is underway. Another amazing Native-made film DAWNLAND documents a truth and reconciliation process for boarding school trauma in the state of Maine. And now perpetrators are also seeking to heal: a Quaker project seeking “right relationship” educates members on how their ‘peace church’ unwittingly contributed to the trauma and how to make repair. With a dozen other Christian denominations, Quakers now seek to make amends for their role in sponsoring boarding schools that were a tool of genocide.

The makers of “R——“ had no access to the Indigenous thought-leaders of today—Pat McCabe and Lyla June Johnston of the Diné, novelist Leslie Marmon Silko of the Pueblo, or Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz who writes about the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680 and other acts of resistance in the region. But the filmmakers did more than we might expect to look honestly at their subjects. Screenwriter Elizabeth Pickett is said to have studied for months on location with Pueblo and Diné peoples to bring their cultures to the screen with some accuracy.

She apparently formed a relationship with the Diné, who allowed the filming of a sacred sand painting. But none of this was enough to change a hardcore colonizing mindset that saw Indigenous cultural practices as backward superstitions. The gifts of resilience and the teachings of both Pueblo and Diné for living sustainably on the earth—which many look to for guidance in the era of climate change—were not recognized or valued in my father’s day.

All the same Pickett and the “R——“ team create an artifact of their times that is beautiful for what it is—not just the wonderful landscapes of Indian Country filmed in Technicolor (with scenes from Wing Foot’s white schooling in contrasting black and white). Not just the skillful—if stereotyped and melodramatic—plot, which I found gripping. More valuable to me than any artistry is the glimpse this film gives into what I think was my father’s mind. His younger brother told me recently of a surprising talk with my dad (probably sometime around the year of this film). My father told him how we Anglos had given the Native people of this continent a bad deal and should be thinking of how to make it up to them. I had no idea he thought such a thing. Somewhere in the midst of all the racist stereotypes and misinformation, a little bit of clarity had leaked through—perhaps with the help of a film like “R——,” and it was left for the next generations to complete the picture.

A Day of Silents presented by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival features “R——“ on Saturday, December 7 at 1:00pm at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. Advance tickets available here.

Live musical accompaniment by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

35mm print courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Copresented by California Film Institute, Eat Drink Films, and Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum

Louise Dunlap is a writer living in Oakland. Her work includes Undoing the Silence, a book for aspiring writers, and a memoir in progress, Inherited Silence about her family’s history in the context of our nation’s racial karma.

Louise Dunlap is a writer living in Oakland. Her work includes Undoing the Silence, a book for aspiring writers, and a memoir in progress, Inherited Silence about her family’s history in the context of our nation’s racial karma.

Dunlap writes: “Since the Free Speech movement of the 1960s, I have been working with writers struggling to express their heartfelt ideas for social change. I’ve worked at many levels–in universities and non-profits, in public sector offices and grassroots community meetings, in U.S. grad programs and civil society organizations from South Africa, Ethiopia and the Sudan. My goals are to help people express challenging truths in ways that can be “heard” and can change outcomes–even in the hard times we face.”

For a selection of articles by Louise Dunlap go here.

See more at www.louisedunlap.net.

Watching films for free–So many of these film resources are offered freely, but they cost money to make. Please consider donating to the organizations that made them—this is always a good idea, but especially when seeking to make repair to a culture that our country’s founders sought to wipe out. East bay residents can offer shuumi (generosity) to the Sogorea Te Land Trust. Other resources at https://resourcegeneration.org/land-reparations-indigenous-solidarity-action-guide/.

THE WELLBRIETY JOURNEY TO FORGIVENESS

The truth about the boarding school era is told in a film through the tears of the Indian people who lived in those days and through their incredibly honest stories, difficult to tell and to hear because they happened to the most helpless—the children they were then. Some of the legacy of boarding schools has also touched their own children, unwitting inheritors of their parents’ pain, as well as whole communities torn apart by intergenerational trauma and how the abuse of former generations is passed on all too often and brushed under the rug, even within families.

Read stories from the journey.

Native-made film DAWNLAND trailer

Watch the documentary that follows native riders on a 330 mile healing journey across South Dakota to Minnesota, in honor of those lost 151 years ago at the end of the Dakota War of 1862, in the largest mass execution ever seen in the United States.

(We are not sure why YouTube has started doing this age-restriction but clicking on “Watch on YouTube” and it will take you to the film.)

Read more on WilderUtopia.

Movies Silently’s Fritzi Kramer writes about “R——.”

Soprano Helen Clark sings the Love Theme Song.

Kevin Brownlow’s The War, the West and the Wilderness is a fascinating look at the making of movies in the silent era with an especially insightful section on western movies.