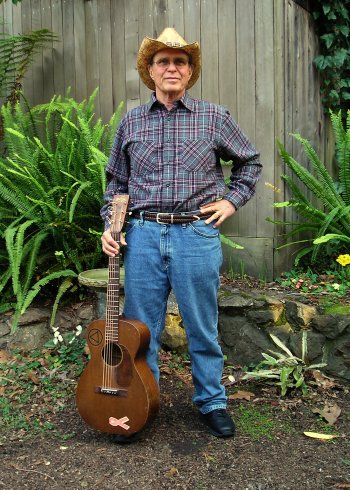

by Country Joe McDonald

John Pirozzi’s documentary film Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten does a great job showing Cambodian popular music from the 1950s up to the present using film clips of people dancing and enjoying the music and interviews with musicians. We get a very good feeling for how the people enjoyed the music, and how the new music from the 1960s impacted the lives of the people.

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten is 105 minutes long. The first half is in color and features the transition of popular music from the 1950s into the new revolutionary music of the 1960s. Then the movie uses black and white footage to show the diaspora from the capital city giving way to mass labor camps and starvation. As the capital city returns after the Khmer Rouge defeat, the film shifts back to color footage of modern times. Throughout it all, we experience this history mostly through the eyes, thoughts, feelings and memories of musicians.

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten is 105 minutes long. The first half is in color and features the transition of popular music from the 1950s into the new revolutionary music of the 1960s. Then the movie uses black and white footage to show the diaspora from the capital city giving way to mass labor camps and starvation. As the capital city returns after the Khmer Rouge defeat, the film shifts back to color footage of modern times. Throughout it all, we experience this history mostly through the eyes, thoughts, feelings and memories of musicians.

His Royal Majesty King Norodom Sihanouk and Her Royal Highness Norodom Monineath (film still courtesy of His Royal Majesty King Norodom Sihanouk)

I found it impossible to view the film with any objectivity. I felt certain that if I was Cambodian I would have been quickly killed for not only being a modern popular musician but a songwriter of social/protest songs. I was surprised to hear ’60s music played excellently by Cambodian musicians and in some cases sung in Cambodian. Without giving a spoiler, I will just say that Santana’s and James Taylor’s music are well represented.

The power of popular music is even today revolutionary just by itself. Like any great invention, it does not need to be sold. It just sells itself. And no matter what pontiffs may say, this working class phenomenon has and still does put fear into despots and fascists all over the planet. Born of the oral tradition of Western African American slaves and the music of their European slave masters, it captured the hearts and minds of all who came in contact with it.

Music, unlike other art forms, cannot be owned. It really cannot be truly bought and sold. Once it is set free upon the world, it soars and morphs into human consciousness, and carries with it an emotional power unlike anything else.

Music, unlike other art forms, cannot be owned. It really cannot be truly bought and sold. Once it is set free upon the world, it soars and morphs into human consciousness, and carries with it an emotional power unlike anything else.

The film had me thinking of Victor Jara, the Chilean singer/songwriter who was beaten to death by the junta soldiers for singing songs the people loved. John Pirozzi’s film has dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Victor Jaras. There are several scenes which brought this home to me. In one, shot in black and white, a young guitar player, backed by several young girl singers, stands in front of a microphone; although we cannot hear the soundtrack, it is obvious from the expressions on the faces of the young audience that this is an ecstatic transformative moment for the performers and the audience. Later in the film, a friend of the young singer explains how he believes that he would have been killed very early on because of his attitude and being such a free spirit. He has never been seen since.

In another scene, one of the musicians explains how in the fields, alone, during the forced labor, they knew no one could hear them, and they sang pop songs that gave them the will to live. It reminded me that during the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese had a famous prison camp that held American prisoners. One of the prisoners told me that the North Vietnamese piped American music into the camp to demoralize them, but when my song was played, it strengthened their will to survive. In another scene from Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten , after returning to the capital city, a musician—now old—is brought to tears upon hearing the music again.

We cannot escape the reality that this music brings a new kind of tradition. It is, to the dismay of much of the status quo, a new genre of music that brings hope. Hope for an end to all the old ways and the birth of a new way of life. This new life is full of hope, joy, spontaneity, invention, sexuality, love, and democracy and freedom. It is leveler of classes and economics and has no room for fascists. It will not tolerate fools. And it cannot be captured and imprisoned and controlled. That is why today rock and roll is outlawed and punishable by prison and death in many countries on the planet.

I was happy to see that what we invented in America in the 1960s found its way to Cambodia and brought to those young Cambodians the same spirit it brought to us. And I wonder how many countries and ethnic groups on the planet also took it to heart and made it their own. And how many more in the future will do so.

My old voice teacher Judy Davis always said that none of the ruling, upper classes contributed to and created pop music. This is the working class gift to the world: pop music. Try to imagine a world without it. Would that be a world you would want to live in? This film chronicles the birth of the new music, how the Khmer Rouge tried to kill it, and how it was reborn again.

DON’T THINK I’VE FORGOTTEN

Opens Friday, May 8, 2015 at the Balboa Theater in San Francisco, Rialto Cinemas Elmwood in Berkeley, Rialto Cinemas Sebastopol in Sebastopol.

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten director John Pirozzi will introduce the 7:15 p.m. screening and do a Q&A on Friday, May 8 at the Balboa Theater; and Saturday, May 9 at the Rialto Cinemas Elmwood.

Country Joe McDonald straddles the two polar events of the 60s—Woodstock and the Vietnam War. The first Country Joe and the Fish record was released in 1965, in time for the Vietnam Day Teach-In anti-war protest in Berkeley, California. He sang one of the great anthems of the era, “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” to an audience of a half-million at the Woodstock Arts and Music Festival in 1969.

Country Joe McDonald straddles the two polar events of the 60s—Woodstock and the Vietnam War. The first Country Joe and the Fish record was released in 1965, in time for the Vietnam Day Teach-In anti-war protest in Berkeley, California. He sang one of the great anthems of the era, “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” to an audience of a half-million at the Woodstock Arts and Music Festival in 1969.

McDonald’s music spans a broad range of style and content. He began his solo career with a collection of Woody Guthrie songs. He went on to produce a musical rendition of the World War I poems of Robert Service, a collection of country and western standards, Vietnam Experience in 1985, Superstitious Blues in 1991 with Jerry Garcia, and an album of songs about nursing in 2002. In 2007, he put together a song-and-spoken-word one-man show about Woody Guthrie, and followed it up with another about Florence Nightingale.

After 48 albums and more than four decades in the public eye as a folksinger, Country Joe McDonald qualifies as one of the best known names from the 60s rock era still performing. He travels the world and continues to sell records. www.countryjoe.com.

Country Joe McDonald home page: www.countryjoe.com.

Country Joe’s Tribute to Florence Nightingale: www.countryjoe.com/nightingale.

Berkeley Vietnam Veterans Memorial: www.ci.berkeley.ca.us/vvm.