by Eddie Muller

Movies brought Charlie Haden and me together. Specifically, it was a Sunday night double-bill at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood, May 13, 2001—a pairing of two John Alton-photographed noirs, The Crooked Way (1949) and Talk About a Stranger (1952) , part of the original Festival of Film Noir I’d created for the American Cinematheque.

While introducing the first feature I couldn’t help noticing a dude in tinted shades about twelve rows back, reacting animatedly to what I was saying. He’d lean forward, hanging on every word, cracking big smiles and gesturing to the blonde at his side. He even threw up a hand to ask a question, as if we were in a classroom, not a movie theatre. The blonde pulled it down, gently. The guy’s rabid enthusiasm was totally out of place in a typically aloof, too-cool-for-school Hollywood film audience.

During intermission this guy—who did seem vaguely familiar—bee-lined toward me in the lobby. “Hey, man, I really dig these movies and all your stories,” he said, offering a soft handshake but no name. “Lemme ask you a question, man—do you remember a movie called The Window ? It starred this little kid named Bobby Driscoll. Man, it was really something. You know whatever happened to Bobby Driscoll, man?”

I hated dropping it on him, but Driscoll had died in 1968, his drug-ravaged body discovered in an abandoned tenement in the East Village, the corpse not ID’d for more than a year. I thought the guy was about to cry: “I knew him, man. We used to hang out together, back in the sixties. He was a beautiful cat.”

The hep-cat lingo was jangling my antennae: “I feel like I know you, man.”

“My name’s Charlie,” he whispered.

The bells went off: “That’s it! You’re Charlie Haden—oh, man!” I blurted. I lauded him effusively, deservedly. He was genuinely thrilled I knew who he was. He introduced me to his wife, singer Ruth Cameron, saying “Dig it, this cat knows my stuff. He’s into my music.”

Haden’s albums, especially the Quartet West discs, In Angel City , Haunted Heart , Always Say Goodbye , and Now Is the Hour had been staples of my office playlist for years, especially during the writing of my first two books on film noir, Dark City and Dark City Dames. I revered Haunted Heart , to me the most lushly romantic musical evocation of classic noir ever recorded.

Such was Charlie’s eagerness that night to talk about films, especially noir, that he braved a post-screening foray into Boardner’s, an old Hollywood watering hole that had succumbed to the numbingly loud “ambient” music of the modern bar scene. That’s how I learned he suffered from tinnitus, a condition in which the victim perceives a painful ringing in their ears. Charlie gamely managed a half hour in the sonic tumult before having to flee. I only learned later that his enduring such cacophony wasn’t only a gesture of camaraderie, but an act of courage.

During a stint at Yoshi’s in Oakland months later Charlie and Ruth came by my house so he could avail himself of the “film vault.” They were both noir fans; he’d just produced her album Roadhouse , on which she performed an array of noir-tinged torch songs. They left that night with two shopping bags full of VHS tapes (remember those?)—obscure films noir I’d amassed researching my books.

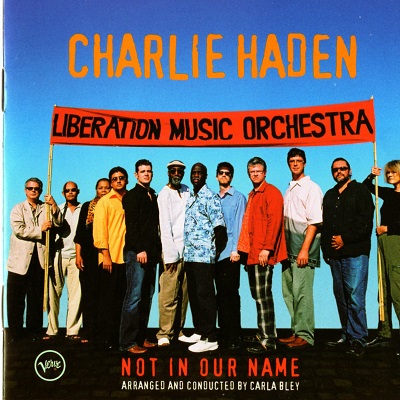

Charlie returned the favor (if not the tapes!) by plugging me straight into jazz history, not just through his music, but via an intimate anecdotal history of his role in it. From the late 1950s and his groundbreaking free jazz work in the Ornette Coleman quartet, through the politicized formation (with Carla Bley) of the fiery Liberation Music Orchestra, through the seductive retrospection of Quartet West and on to his sublime collaborations with artists such as Keith Jarrett, Paul Motian, Pat Metheny, Egberto Gismonti, and Gonzalo Rubalcaba (their Nocturne might be the most swoon-inducing record I’ve ever heard), Charlie allowed me to experience jazz more deeply than I ever had.

He once bailed me out at a particularly daunting film show, where I’d agreed to host irascible composer David Raksin. I learned a few days before the show that Raksin planned on using the screening of Force of Evil as a bully pulpit from which to excoriate the film’s director, once-blacklisted Abraham Polonsky. Raksin hated Polonsky, both artistically and politically, and was eager to vilify him. Charlie agreed at the last minute to co-host the event with me—the ace up my sleeve, as it were—and his overwhelming musical knowledge, insight, and reverence humbled Raksin; the interview became a celebration of the art of film scoring, not the vituperative bout of score settling Raksin had intended.

It seemed inevitable that I’d invite Charlie and Quartet West to play a benefit concert for the fledgling Film Noir Foundation at NOIR CITY in 2006, especially since the festival had ditched the Castro Theatre for new digs at the Palace of Fine Arts, which was really a performing arts venue more than movie theatre. I was also at the time in discussions with SFJAZZ about curating a jazz-noir film series. When I mentioned to executive director Randall Kline that I wanted to produce a show with Charlie, he offered a wry smile and said, “You really think you can handle that?”

Apparently my friendship with the bass-playing legend hadn’t yet exposed me to his legendary reputation for being “difficult.” I got an inkling of it when the contract arrived for the show, with its densely detailed rider: the demands for the performance space were extraordinary, including the exact width of the tri-part plexiglass shield he’d need to play behind, the technical specifics of all the equipment used—right down to the height of the shag on the carpet covering his riser. I also had to rent a Ford Excursion—the lone one I could find in San Francisco—because it was the only passenger vehicle large enough to accommodate his double bass. None of this really bothered me; such were the necessities of artistic genius. … Right?

Things began getting complicated as the date approached. Drummer Larance Marable was already out, no longer part of the charter group that comprised Quartet West. But then saxophonist Ernie Watts was offered a better gig; Charlie championed local sax whiz Joshua Redman as a replacement (after all, Charlie had played, thirty-five years earlier, with Josh’s dad, Dewey), but I wasn’t thrilled about promoting a Quartet West show featuring only half the genuine quartet. Charlie pressed it, craving the gig. My frustration grew as union regulations at the Palace started threatening the quick turnaround needed between the film screenings and the live performance. On top of all this, I was trying to sell a big-ticket jazz show to an audience used to paying ten bucks for a double-feature: advance sales were slow. Then the last domino fell—pianist Alan Broadbent left on tour with Diana Krall. Quartet West was down to its founder.

That’s when I learned the first lesson of concert producing: “We’re not canceling, we’re postponing.”

I found an open date on everyone’s calendar three months down the road and switched the concert venue to Herbst Theatre. Watts and Broadbent were back in. The show would go on, albeit disconnected from the film festival it was meant to support.

The night before the concert I took Charlie, Ernie Watts, and Alan Broadbent to dinner at Postrio in the Prescott Hotel, where they’d been ensconced. It was a fun evening, during which I got a sense of how his band-mates long had tolerated Charlie’s eccentricities, which extended to his eating habits. Persnickety palettes are common in the Bay Area, but Charlie had an especially endearing—some might say enervating—way of navigating a menu. Watts and Broadbent merely watched with bemusement as Charlie commenced the epic task of ordering dessert.

“This fruit cobbler thing, man,” he asked the waiter, “Is it … tart?”

“A bit,” replied the waiter. “But not so much so.”

“And how about this sorbet, man? What’s that like? Is it … tart?”

“Yes, definitely, both the lemon and the raspberry. Yes. Either’s nice. Very tart.”

“Oh, okay, man. How about this torte? Is it very … tart?”

“Uh, no. It’s blueberries, in a nice custard, you know? Delicious.”

There were eight desserts listed. He was going to ask about every one.

“And, uh, the key lime p—”

“That’s definitely gonna be tart,” I cut in. He was driving me, and the waiter, crazy. I had to blurt out: “Charlie, quick question that might help: tart—good or bad?”

The world’s greatest jazz bassist seemed all of eight years old as he said, “Oh, man—tart is bad!”

Of course, after all that: “I’ll skip the dessert, man.”

The next morning I picked up drummer Tim Pleasant at the airport. Charlie had brought him on as replacement for Marable. We headed back toward the city in the massive Excursion I was now piloting everywhere. Tim sat in the backseat with headphones clamped on and sheet music spread out all around him. He was visibly anxious.

“Cramming?” I asked.

“Never played with these guys before,” he replied, studying the charts. Holy shit.

During that afternoon’s rehearsal I experienced the “difficult” Charlie first-hand. He ran the sound engineer through a hellacious trial, painstakingly modulating differences in levels that were indistinguishable to my ears. I couldn’t figure out if he was genuinely concerned about the technical issues, or was using a roundabout tactic to test out Tim Pleasant. Alan Broadbent, a serene guy with a dry and wry sense of humor, simply sat at the piano and smiled—he’d experienced this a million times before. Ernie Watts ventured deep into the building’s bowels to warm up by himself. Behind the drum kit, Pleasant was as calm as a Little Leaguer trying out for the Yankees. Not in a million years did I expect so much tension from a bunch of jazz cats.

After about 90 minutes of this discomfort and uncertainty, Charlie found me in the wings and dropped on me one of the most dispiriting (if hilarious) lines I’ve ever encountered: “Hey, man—what do you take for nausea?”

I had to dispatch my pal David Corbett to find a pharmacy that dispensed powered magnesium, the only cure Charlie felt might work in the few hours before show time. David returned within the hour, but with magnesium capsules—which he and I carefully separated, collecting the contents into a single vial of the “powered magnesium” Charlie had requested. This is what “producing” is all about.

Everything was perfectly in place for a totally disastrous evening.

But—of course—it was magical. Whatever personal pressures and peccadilloes existed within, or between, these guys, when it came to making music everything else fell away. By the time they dug deeply into Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman”—a signature composition of the free jazz movement Charlie had helped originate, my heart was practically bursting from being intimately involved in something so majestic. We didn’t make a cent from the “benefit,” but in the end I didn’t regret a moment of it. You are lucky in this life to be in proximity to such greatness.

On the drive back to the hotel, Tim Pleasant, in the back seat next to Broadbent, looked happy but a little pensive, wondering if he’d made the grade. Before we’d gotten out of the parking lot, Charlie, riding shotgun, said: “Tim—next time we play together, man, I probably won’t even need the plexi.” Broadbent showed Pleasant a big “How do you like that!” expression. They traded some skin on the down-low.

Charlie, still buzzing from the show, wanted to grab a late meal after the other guys had packed it in. We found a place off Union Square and I prepared for another of his in-depth interrogations of the menu. Here was a guy whose trip had taken him from a boyhood of traditional country music to the outer edges of improvisational modern jazz and every variation in-between, contemplating all the nuances and consequences of his next meal, one more out of a hundred thousand in his life. For some reason, I was compelled to lob a “big one” into the small, hushed booth:

“So what’s it all about, Charlie? You’ve been at it a lot of years. What’s it all amount to?”

Charlie set down the menu and looked right into me. His answer had the assurance, elegance, and profundity of his bass lines: “It’s about beauty, man. It’s about putting beauty into the world.”

Reading the tributes that have poured in since his death, the outpouring of love and appreciation for his generous nature, collaborative spirit, and unflagging positivity, one might wonder what drew Charlie to noir and its fatalistic ethos. But then you have to realize that Charlie Haden was done in by a post-polio syndrome long dormant in his body. It was the effects of that childhood disease that early on ended his career as a vocalist and forced him to take up the bass. During all the wondrous things Charlie accomplished in his life, the thing that would kill was always there, lurking—like Edmond O’Brien in DOA or Ben Gazzara in Run for Your Life . You can’t escape. The past always catches up with you.

But in the meantime, you can be a hero. And that’s what Charlie was, to musicians and listeners the world over.

As I write this, word comes of a civilian passenger jet shot down over Ukraine. The Israelis and Palestinians are trading missiles in Gaza. Endless indignities to the human spirit and soul rage on, Comrade Haden. But you accomplished your mission. Time finally ran out, but look at what your talent and perseverance achieved, look at what you left behind!

In the face of all the world’s ugliness and evil, you conjured beauty, man—and it will soar forever.

We encourage you to buy Charlie Haden CDs and DVDs from local music stores or you can purchase them through our affiliate programs at either Indiebound or Amazon.com.

Terry Gross’ tribute to Haden is terrific. Listen on (Fresh Air). Rambling Boy, a wonderful 90 minute doc is online from German TV.

Eddie Muller is a writer, filmmaker, and noted noir historian. His books include Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir ; Dark City Dames: The Wicked Women of Film Noir , and The Art of Noir: Posters and Graphics from the Classic Film Noir Era. He has recorded numerous audio commentaries for DVD reissues of classic noir films. Muller’s crime fiction debut, The Distance was named “Best First Novel” of 2002 by the Private Eye Writers of America. He is co-author of the bestseller Tab Hunter Confidential. Find Eddie Muller and Noir City at: EddieMuller.com

Eddie Muller is a writer, filmmaker, and noted noir historian. His books include Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir ; Dark City Dames: The Wicked Women of Film Noir , and The Art of Noir: Posters and Graphics from the Classic Film Noir Era. He has recorded numerous audio commentaries for DVD reissues of classic noir films. Muller’s crime fiction debut, The Distance was named “Best First Novel” of 2002 by the Private Eye Writers of America. He is co-author of the bestseller Tab Hunter Confidential. Find Eddie Muller and Noir City at: EddieMuller.com

Eddie Muller © 2014

thanks for this! the tributes to the great Charlie Haden justifiably keep coming: Terry Gross on Fresh Air did a particularly good job (http://tinyurl.com/nfm7zqr) and there’s Rambling Boy, a wonderful 90 minute doc online from German tv that’s worth watching for its depth and breadth (http://vimeo.com/83239232).

Thanks, Eddie, for your sweet tribute to a giant of music. I saw Charlie play several transcendent concerts at Keystone Korner in North Beach. Indeed, it’s all about beauty. . .

Wonderful post! I am still mourning the loss of Mr. Haden. Thank you for a very interesting story about an area most of us fans never see…the mechanics of putting on a show and dealing with artists. I laughed about Charlie’s restaurant ordering habits..as a one time bartender, I recognize the type! The tributes pouring out of the jazz world show just how much he was admired and respected..From saxophonist David Liebman, on Facebook:

“From Blanton to Pettiford to Ray Brown, Charlie Haden was the next step along with Scott LaFaro in re-defining the role of the bass. “Time, no changes” was his world, but he could deal with harmony very easily. It was his linear, highly melodic and counterpoint phrasing that was uniquely Charlie that found its home with Ornette. We recorded “My Goals Beyond with John McLaughlin in the early ’70s and Charlie is also on my recording Sweet Hands a bit later. Charlie’s solos were invariably plainly stated, apparently “simple,” obviously melodic, but most of all played with a passionate feeling and deep tone. We talked a few times in the past years about post polio syndrome (which several well-known people have encountered), trying to find someone, somewhere, who could treat it, apparently to no avail. He went down as a warrior, just the way he played.”