By Vince Keenan

The 51st Seattle International Film Festival drew to a close on May 25, with a selection of entries available via streaming through June 1. At this year’s fest, I paid particular attention to nonfiction titles spotlighting the troika of subjects that matter most to EatDrinkFilms readers. Let’s begin with a libation.

Wine has its sommeliers, beer its cicerones. As the craft cocktail revolution took hold in the aughts, six authorities on spirits launched a program that would provide similar certification to bartenders.

BAR (United States, 2025) tracks the 2023 class attending the Beverage Alcohol Resource 5-Day Program, held at the Culinary Institute of America’s main campus. The course consists of three days of instruction in sessions lasting up to sixteen hours, followed by two rigorous days of testing that include a written exam, a practical one (preparing half a dozen drinks in ten minutes, including one original concoction), and a blind tasting of both spirits and cocktails. Director Don Hardy’s film surveys five candidates from a broad range of backgrounds, among them a radiologist who dreams of opening his own watering hole; a woman who tends bar to finance her pursuit of a doctorate in psychology and aspires to raise awareness of mental health issues in the hospitality industry; and a young mixologist covering the cost of her participation via work/study, hustling to complete back-of-house tasks in addition to cramming. It’s easy to root for every member of this gregarious quintet, because BAR’s true subject is the openness and camaraderie of the bartending community. Dale DeGroff, one of the BAR program’s founders, notes that hospitality offers a home for individuals who don’t readily fit in elsewhere, while his colleague Steven Olson says bartending draws those who live to make people happy. Hardy also pointedly features excerpts from a panel on diversity, still a welcome and essential quality in this world. BAR is an engaging documentary, the question of who emerges from the gauntlet triumphant lending an element of suspense.

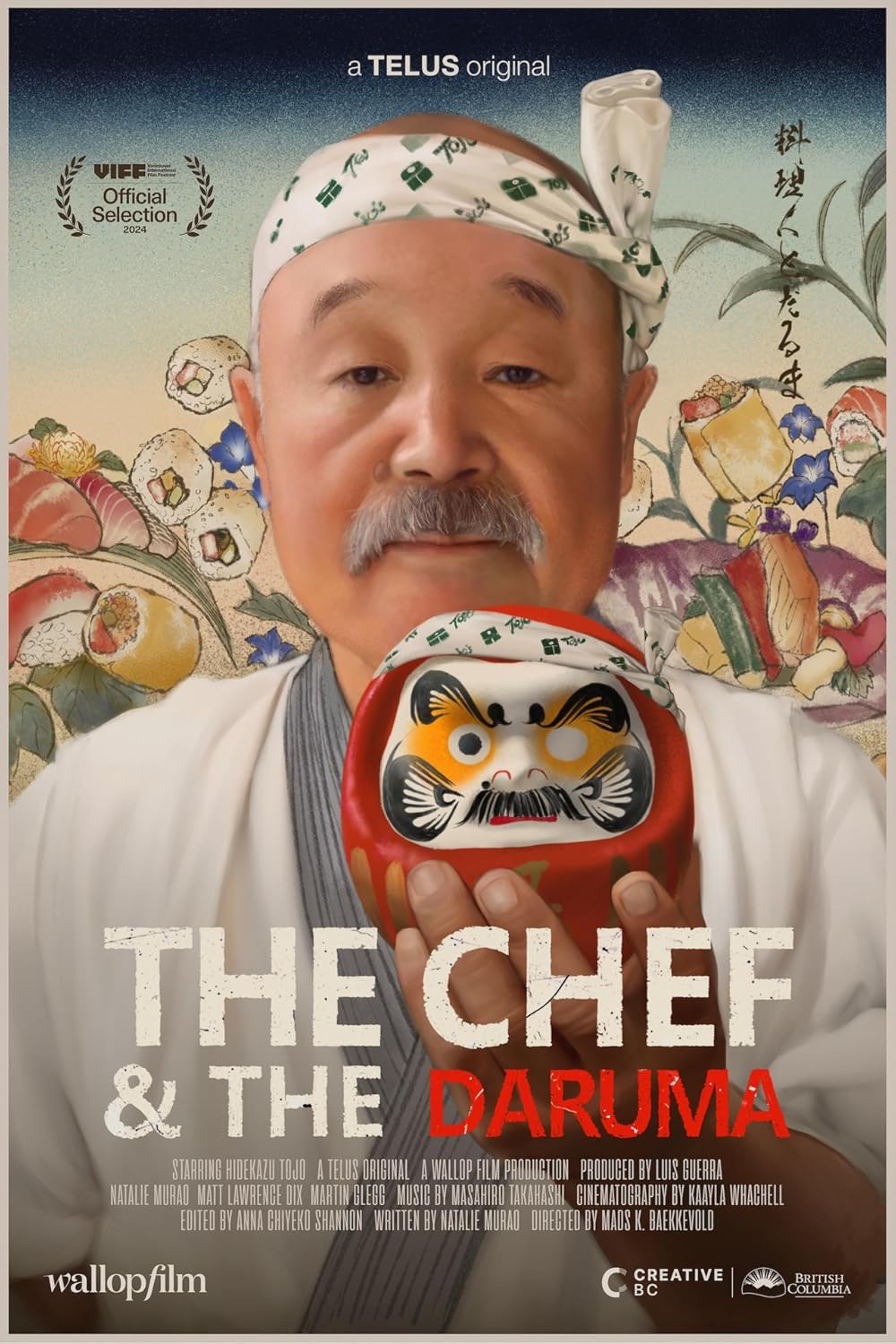

The Chef & The Daruma (Canada, 2024) also benefits from a built-in structure. Director Mads K. Baekkevold and writer Natalie Murao frame the story of Vancouver, BC sushi maestro Hidekazu Tojo through his use of daruma dolls. Tojo explains that each of the Japanese Buddhist figurines represents a promise made to pursue a dream. Seven of these goals, among them Feed Those Around You and Share Your Passions, come into play as Tojo recounts his life.

He arrived in Vancouver in 1971, making a study of what Canadians liked to eat and incorporating those ingredients in Japanese fashion. Tojo is among several chefs who claim to have invented the California roll. He presents a sturdy case, saying he developed what he initially called “the Inside Out roll” to conceal sushi elements then unfamiliar to Western diners, like seaweed. Despite the engaging daruma doll device, the documentary becomes disjointed whenever it ventures away from Tojo himself. A section on the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II is potent but only tangentially linked to the main narrative, while a detour into the history of sake is so brief that it frustrates instead of illuminates. Tojo’s moving pilgrimage to a former salaryman’s spartan restaurant devoted to dashi, a family of broths common to Japanese cuisine, is weakened by the film’s failure to explain what dashi is. Still, Tojo makes a charismatic guide, the embodiment of his belief that “Food is a tool that can make people happy.”

He arrived in Vancouver in 1971, making a study of what Canadians liked to eat and incorporating those ingredients in Japanese fashion. Tojo is among several chefs who claim to have invented the California roll. He presents a sturdy case, saying he developed what he initially called “the Inside Out roll” to conceal sushi elements then unfamiliar to Western diners, like seaweed. Despite the engaging daruma doll device, the documentary becomes disjointed whenever it ventures away from Tojo himself. A section on the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II is potent but only tangentially linked to the main narrative, while a detour into the history of sake is so brief that it frustrates instead of illuminates. Tojo’s moving pilgrimage to a former salaryman’s spartan restaurant devoted to dashi, a family of broths common to Japanese cuisine, is weakened by the film’s failure to explain what dashi is. Still, Tojo makes a charismatic guide, the embodiment of his belief that “Food is a tool that can make people happy.”

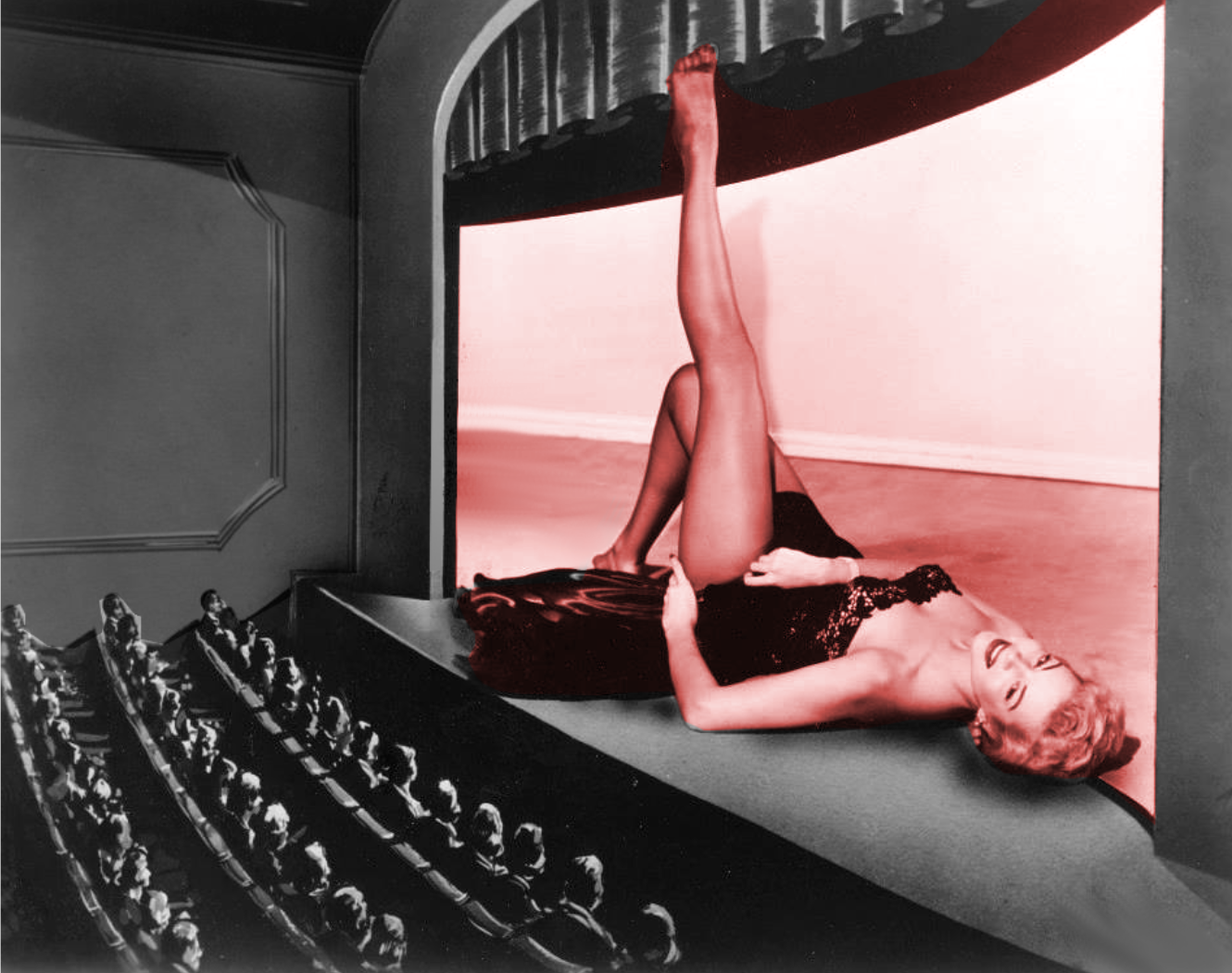

Shifting to cinema about cinema, Know Her Name (Canada, 2024) is an ambitious, sprawling enterprise that plays more like a syllabus for a life-altering film studies course than a cohesive whole. Director Zainab Muse aims to tell nothing less than the story of women filmmakers and how their many contributions have been consistently neglected when not outright erased. The term “historical amnesia” is repeatedly invoked over an eighty-minute running time too short to do justice to the many topics Muse raises. Critiques of capitalism and patriarchy jockey with fleet biographical sketches of pioneering filmmakers (Alice Guy-Blaché), women who nevertheless persisted during the early Hollywood era (Dorothy Arzner and Lois Weber), and trailblazing independent artists (Esther Eng and Marion E. Wong).

Muse enlists a chorus of directors including Mary Harron (American Psycho) and Deepa Mehta (the Elements trilogy) along with the generations that followed them to testify, yet issues that expressly affect them, like Harron’s cofounding of the Missing Movies initiative upon discovering that her film I Shot Andy Warhol (1996) was unavailable for streaming because of cloudy distribution rights, receive glancing treatment. Heartfelt and motivated by justifiable anger, Know Her Name is a primer on a monumental matter.

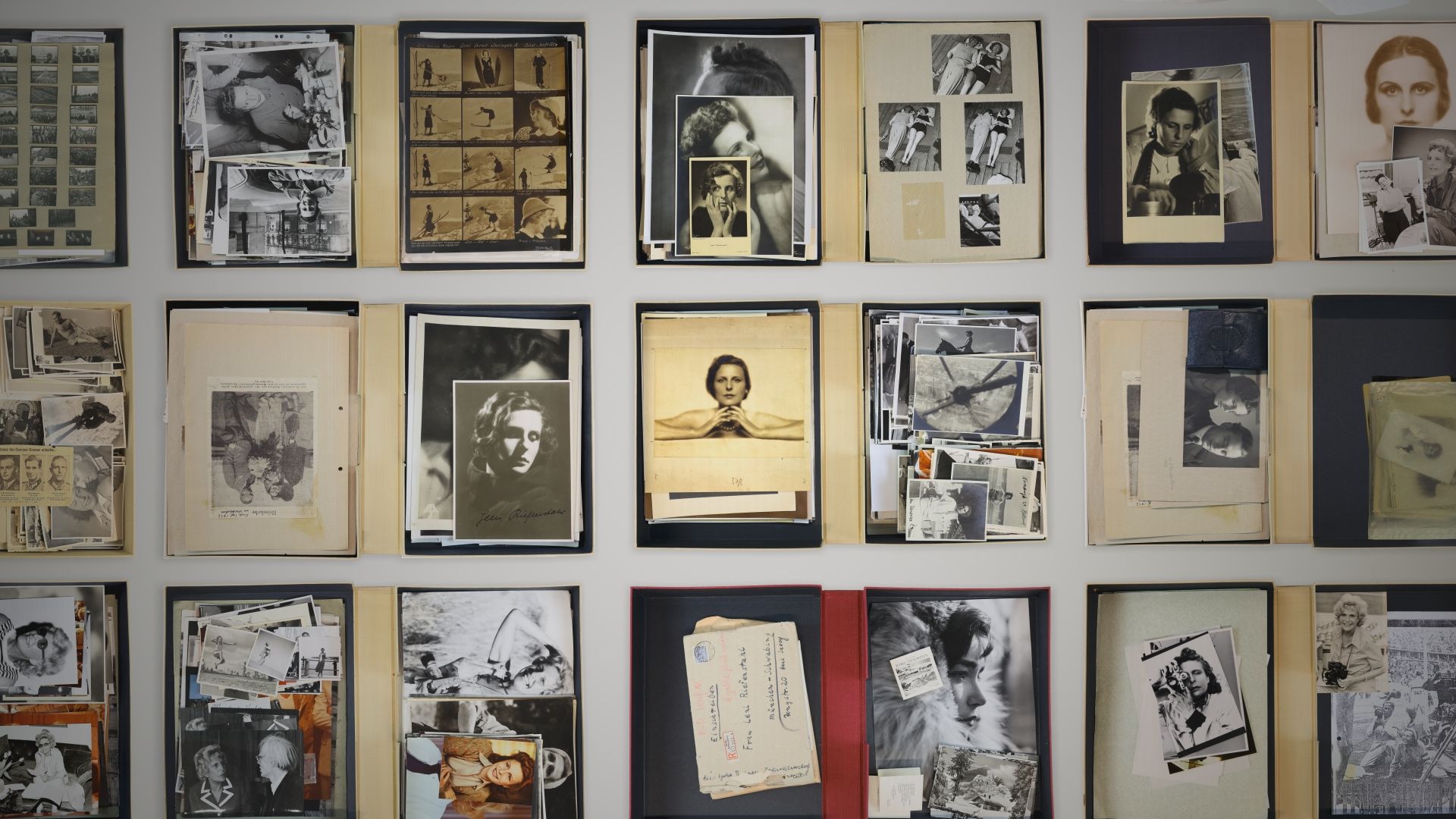

Arguably the most famous female filmmaker is the sole focus of a documentary at SIFF. Riefenstahl (Germany, 2024) is not the first movie to consider the tainted legacy of Leni Riefenstahl, whose films Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938) served as propaganda for the Third Reich. But it is the first to make extensive use of Riefenstahl’s own archive, excavating the past that she preserved to “document 101 years of her life” and deploying it as evidence in a damning case against her.

Writer/director Andres Veiel wastes no time; in Riefenstahl, the credits cast shadows. He makes canny use of individual frames of her film or still photographs: a handshake with Adolf Hitler, a warm look shared with Albert Speer, whom she regarded as a fellow artist and peer even after his prison sentence for war crimes. Riefenstahl’s festering resentment that her accomplishments are inseparable from the fascist culture they glorified registers strongly; she would spend decades of those 101 years shifting goalposts and mounting legalistic arguments to excuse herself. The film includes incredible footage of a 1970s German talk show appearance Riefenstahl made alongside a woman of the same age who resisted the Nazis. The look of muted fury on Riefenstahl’s face when her fellow guest accuses her of making “Pied Piper films” is terrifying. Riefenstahl logged every response that appearance received, recording each supportive telephone call and filing dissenting opinions under the telling category of “Those with different views, Communists, Jews, etc.” Veiel also finds a wealth of material in outtakes from Ray Müller’s justly acclaimed The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (1993). The earlier documentary was long regarded as definitive, but Veiel unearths clips of Riefenstahl engaged in diva-level badgering, haranguing Müller about what subjects he can raise and how he can phrase questions. Veiel’s film occasionally overreaches, as when it weakly contends that a misunderstanding of Riefenstahl’s direction during a brief stint as a “war correspondent” in 1939 may have directly led to the deaths of almost two dozen Jewish prisoners in Poland. But overall, Veiel rebuts his subject’s claims with relentless precision. He counters her insistence that the Roma children she took from Nazi camps to cast as extras in her final narrative feature Lowlands (shot during WWII, released in 1954) all survived the war when in fact most of them were killed at Auschwitz, and shows her lying about the manner in which she chronicled the lives of the Nuba tribespeople of Sudan, photographic images which now feel opportunistic. Veiel’s exploration of how one person’s unshakeable conviction in their version of the truth, including their own victimhood, can distort the record feels newly and glaringly relevant.

Alexandre O. Philippe, a specialist in films about films, has already made documentaries about Psycho (1960) and Alien (1979), among others. In Chain Reactions (United States, 2024), he turns his attention to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), described as a “grindhouse American masterpiece” by one of his interview subjects, filmmaker Karyn Kusama (Jennifer’s Body, Destroyer). The m-word is not used lightly; by the end of Chain Reactions, admirers of the horror classic directed and cowritten by Tobe Hooper have compared it to the work of Ingmar Bergman, Stan Brakhage, and Andrei Tarkovsky—and what’s more, you understand why. (Hooper’s cowriter Kim Henkel is an executive producer of the documentary.) In five separate chapters, Philippe allows a prominent TCM fan to expound on the hold Hooper’s film has over them.

No one who has read Silver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to Film (2015) will be surprised by the incisive criticism from actor/comedian Patton Oswalt. He singles out the unnerving sense that “the killers in the movie have stolen a camera and they’re filming all this,” calls the “porch scene” when one of the teenaged victims almost escapes from Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface a dividing line for horror film fans, and offers a genuinely disturbing theory about the root of the madness propelling the action. Auteur Takashi Miike (Audition, Ichi the Killer) only saw the movie, known as The Devil’s Sacrifice in Japan, because he couldn’t get into a sold-out revival of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), and speculates on the course his life might have taken otherwise. The yellowed, “terribly shitty” VHS prints of TCM available in Australia allow critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas to consider it an American cousin to Aussie films like Wake in Fright (1971). Surprisingly, Stephen King’s segment proves the lightest on insight, although he does say that good horror is “supposed to go too far.” Kusama rounds out the company by discussing Hooper’s opus as an explicitly political work, considering Leatherface and his clan as displaced workers and describing the harrowing family dinner scene as the “saddest, scariest depiction of broken masculinity.” All five analysts acknowledge the unexpected beauty in Hooper’s film and their compassion for the characters typically viewed as the villains; as Heller-Nicholas puts it, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a “home invasion” film when viewed from Leatherface’s perspective. Fifty years and multiple iterations later, Hooper’s independent original remains a landmark and an unlikely source of empathy.

BAR and Know Her Name are among the thirty films streaming as part of the Seattle International Film Festival through June 1. The links for each film take you to the film’s listing in the catalog with more information about each film.

Beyond the EatDrinkFilms categories here are some other thoughts about this year’s festival.

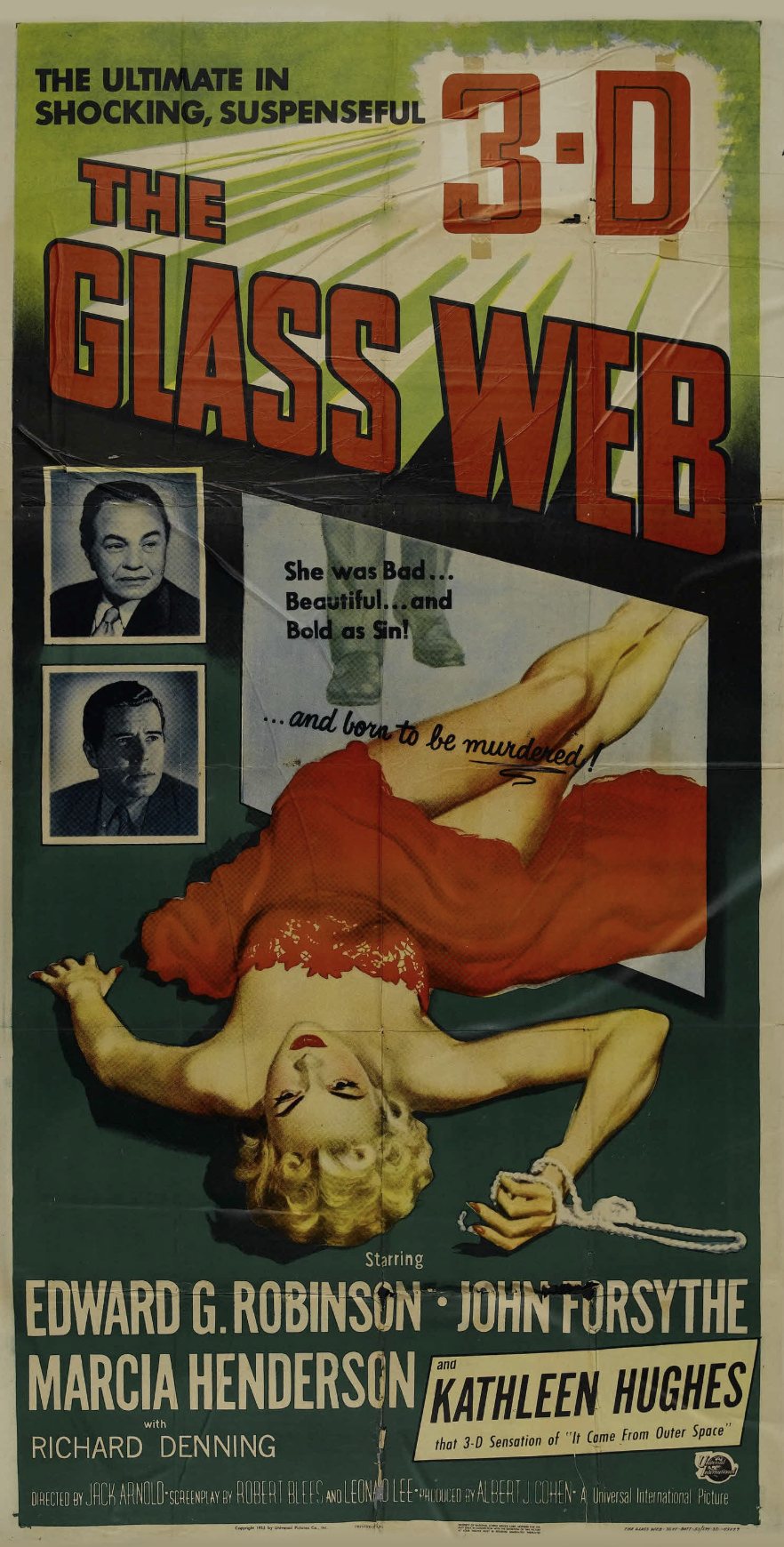

My personal highlight of the 2025 Seattle International Film Festival was not some new, obscure discovery but a curio over seventy years old. As part of its archival program, the festival screened a recent restoration of The Glass Web (1953), one of the handful of noir films shot using the 3-D process. I appreciated the visual gimmickry, but the nifty murder plot provided all the fireworks I required.

(1953), one of the handful of noir films shot using the 3-D process. I appreciated the visual gimmickry, but the nifty murder plot provided all the fireworks I required.

John Forsythe stars as Don Newell, who cranks out scripts for the reality TV forerunner Crime of the Week. His eye wandered from his typewriter long enough for him to have had a dalliance with ambitious actress Paula Rainer (Kathleen Hughes). A chastened Don has returned to his wife, but Paula blackmails him. Don drains his kids’ accounts at the credit union and arrives at Paula’s pad to pony up—only to find her dead. He’s scrambling to hide his history with the victim when Henry Hayes (Edward G. Robinson), the wily ex-crime reporter turned researcher who has his eye on Don’s job, convinces the show’s producers that their season finale should tackle the Rainer case.

The Glass Web is no masterpiece, just a lot of nasty fun. It helps to be in the hands of Jack Arnold, the Spielberg of early stereoscopic cinema, who directed four 3-D features in the 1950s including Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Here he uses the technology mainly to show depth of field, most effectively in scenes set in the TV studio complex. It’s ironic that the movie gives us a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the nascent days of television considering that 3-D was developed to coax audiences away from the small screen and into theaters. There’s a begrudging sequence packed with “comin’ at ya!” gags, Don wandering the streets bemoaning his fate as various objects tumble toward the camera. The restored 3-D looks terrific. Kathleen Hughes, a formidable femme fatale, was cast on the strength of her brief appearance in It Came from Outer Space (1953), another of Arnold’s 3-D features. This led Universal to crown her “Miss 3-D 1953.” The day after SIFF’s screening of The Glass Web, Hughes died at age 96. My Film Noir Foundation colleague Alan K. Rode wrote a reminiscence of the actress for Variety.

The restored 3-D looks terrific. Kathleen Hughes, a formidable femme fatale, was cast on the strength of her brief appearance in It Came from Outer Space (1953), another of Arnold’s 3-D features. This led Universal to crown her “Miss 3-D 1953.” The day after SIFF’s screening of The Glass Web, Hughes died at age 96. My Film Noir Foundation colleague Alan K. Rode wrote a reminiscence of the actress for Variety.

My favorite SIFF movie of the past decade is The Guilty (2018). In this Danish drama, a compromised cop busted down to responding to 911 calls seizes on a communication from a woman in distress as a bid at redemption. The action never leaves the call center but remains relentless; Gustav Möller deservedly won the festival’s Golden Space Needle Award for Best Director that year. The film was remade, with Antoine Fuqua (Training Day) steering Jake Gyllenhaal through a script by True Detective’s Nic Pizzolatto, but I haven’t seen it. Möller’s original left that deep a mark.

Möller returns to SIFF with his follow-up feature. Sons (Denmark/Sweden, 2024) serves up more tension in tight quarters, this time in prison. Guard Eva Hansen (Sidse Babett Knudsen, star of the international hit TV series Borgen) is the mother hen of her cell block, brooking no nonsense even as she asks after each inmate’s sleep and teaches her charges deep breathing. When she spies Mikkel (Sebastian Bull) being processed into the high-security wing, she arranges a transfer, because years ago the new prisoner murdered her son. She sets out to get revenge, her matronly qualities leading everyone to underestimate her except the target of her aggression; soon, they’re locked in a clandestine battle of wills. Their duel builds toward a catharsis that unfortunately never comes. Möller may intend for it to be thwarted, suggesting that both characters are imprisoned by choices made long before they wound up behind bars, but the ending still feels unresolved. Two sterling lead performances carry audiences past that disappointment and several logical inconsistencies. Eva has dialed her grief down so low that it’s startling whenever Knudsen unleashes it, and while Bull may resemble a proto-Mads Mikkelsen, the quicksilver play of emotions over a face that is brutish one second and childlike the next calls to mind early turns by Joaquin Phoenix.

Möller returns to SIFF with his follow-up feature. Sons (Denmark/Sweden, 2024) serves up more tension in tight quarters, this time in prison. Guard Eva Hansen (Sidse Babett Knudsen, star of the international hit TV series Borgen) is the mother hen of her cell block, brooking no nonsense even as she asks after each inmate’s sleep and teaches her charges deep breathing. When she spies Mikkel (Sebastian Bull) being processed into the high-security wing, she arranges a transfer, because years ago the new prisoner murdered her son. She sets out to get revenge, her matronly qualities leading everyone to underestimate her except the target of her aggression; soon, they’re locked in a clandestine battle of wills. Their duel builds toward a catharsis that unfortunately never comes. Möller may intend for it to be thwarted, suggesting that both characters are imprisoned by choices made long before they wound up behind bars, but the ending still feels unresolved. Two sterling lead performances carry audiences past that disappointment and several logical inconsistencies. Eva has dialed her grief down so low that it’s startling whenever Knudsen unleashes it, and while Bull may resemble a proto-Mads Mikkelsen, the quicksilver play of emotions over a face that is brutish one second and childlike the next calls to mind early turns by Joaquin Phoenix.

When you cowrite a series of mysteries featuring Edith Head as a detective, you are obligated to see any movie set in a costume shop. Diamonds (Italy, 2024) primarily plays out at a theatrical atelier in 1974 Rome run by two sisters. When an Oscar-winning costume designer asks them to take on the wardrobe for the stars of an epic period film, the more hard-driving of the siblings (Luisa Ranieri) pushes to do the clothes for the entire company.

Naturally, all the women in her employ, played by an ensemble of over a dozen of Italy’s top actresses, put their lives on hold, because … art. Diamonds is a groaning buffet, director/cowriter Ferzan Özpetek tossing in traumas—Political unrest! Family tragedy! Domestic violence!—like fistfuls of spice into a sauce, compressing a telenovela’s worth of plot into 135 minutes punctuated with not one but two breaks for the cast to burst into song. Plus there’s a bizarre meta framing device with Özpetek first assembling his leading ladies for a family meal to propose the film, then hosting a script reading that turns into a conversation about death, and finally wandering the now-empty sets recalling favorite bits of dialogue. Diamonds was a smash hit in its native land, and it’s easy to understand why. Flashy and superficial, the damned thing keeps moving, simply because it has to. And it’s a bonanza of dazzling costumes, particularly the chic outfits worn by Ranieri. It’s not a good movie. It would be a better one with a pitcher of negronis on hand.

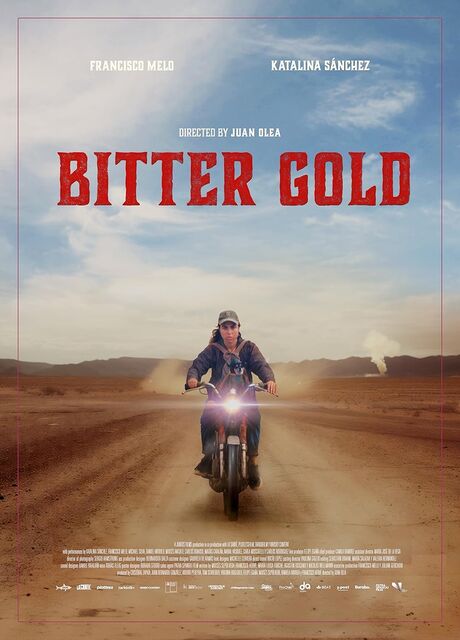

Bitter Gold (Chile/Mexico/Uruguay/Germany, 2024) is exactly the kind of film one hopes to stumble on at a festival, unheralded, unpretentious, and riveting. Fittingly, it’s about searching for the title element. 16-year-old Carola (Katalina Sánchez) leads a hardscrabble existence with her father Pacífico (Francisco Melo) in the deserts of northern Chile, running a wildcat copper mine. Every morning, they ferry their surly crew into the barren wastes, Carola monitoring expenses and cooking for the team.

When Pacífico is critically injured following an ambush by a drunken employee, Carola takes his place. She pretends her father is away on business, scrambling to keep the threadbare operation afloat and fending off rivals who sense an opportunity in Pacífico’s absence. There are shades of neo-noir and the western in this thriller, its tight script revealing so much by implication. Director Juan Francisco Olea heightens the suspense with lingering shots of the desolate, almost-alien landscape to emphasize how isolated the characters are; no one is coming to their rescue. Anchoring it all is Sánchez’s remarkable performance. Her fierce and resourceful Carola is bluffing almost every second she’s onscreen, even in scenes with her father when she’s too frightened to admit how thinly she’s been stretched—and how bad he looks. “Wherever there’s gold, there’s always a somewhat bitter taste,” Pacífico tells her as a piece of practical mining advice. Turns out it’s applicable everywhere.

When Pacífico is critically injured following an ambush by a drunken employee, Carola takes his place. She pretends her father is away on business, scrambling to keep the threadbare operation afloat and fending off rivals who sense an opportunity in Pacífico’s absence. There are shades of neo-noir and the western in this thriller, its tight script revealing so much by implication. Director Juan Francisco Olea heightens the suspense with lingering shots of the desolate, almost-alien landscape to emphasize how isolated the characters are; no one is coming to their rescue. Anchoring it all is Sánchez’s remarkable performance. Her fierce and resourceful Carola is bluffing almost every second she’s onscreen, even in scenes with her father when she’s too frightened to admit how thinly she’s been stretched—and how bad he looks. “Wherever there’s gold, there’s always a somewhat bitter taste,” Pacífico tells her as a piece of practical mining advice. Turns out it’s applicable everywhere.

SIFF announced this year’s award winners on Sunday, and thirty films are available via streaming through June 1.

Vince Keenan is one half of classic Hollywood mystery writer Renee Patrick, the other half being his wife Rosemarie Keenan. He is the author of DOWN THE HATCH: ONE MAN’S ONE YEAR ODYSSEY THROUGH CLASSIC COCKTAIL RECIPES AND LORE and the former editor-in-chief of Noir City, the magazine of the Film Noir Foundation. Vince has written about cocktails and movies for EatDrinkFilms. His Substack newsletter is Cocktails and Crime. You can also keep up with his activities at his blog. He started his career as a theater usher and never looked back. As a finalist on the IFC game show Ultimate Film Fanatic celebrity judge Henry Rollins called him “presidential.”

Hollywood mystery writer Renee Patrick, the other half being his wife Rosemarie Keenan. He is the author of DOWN THE HATCH: ONE MAN’S ONE YEAR ODYSSEY THROUGH CLASSIC COCKTAIL RECIPES AND LORE and the former editor-in-chief of Noir City, the magazine of the Film Noir Foundation. Vince has written about cocktails and movies for EatDrinkFilms. His Substack newsletter is Cocktails and Crime. You can also keep up with his activities at his blog. He started his career as a theater usher and never looked back. As a finalist on the IFC game show Ultimate Film Fanatic celebrity judge Henry Rollins called him “presidential.”

Become a regular reader of Vince Keenan’s Cocktails and Crime! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support his work.

Love this foodie-film roundup—can’t wait to binge these picks!