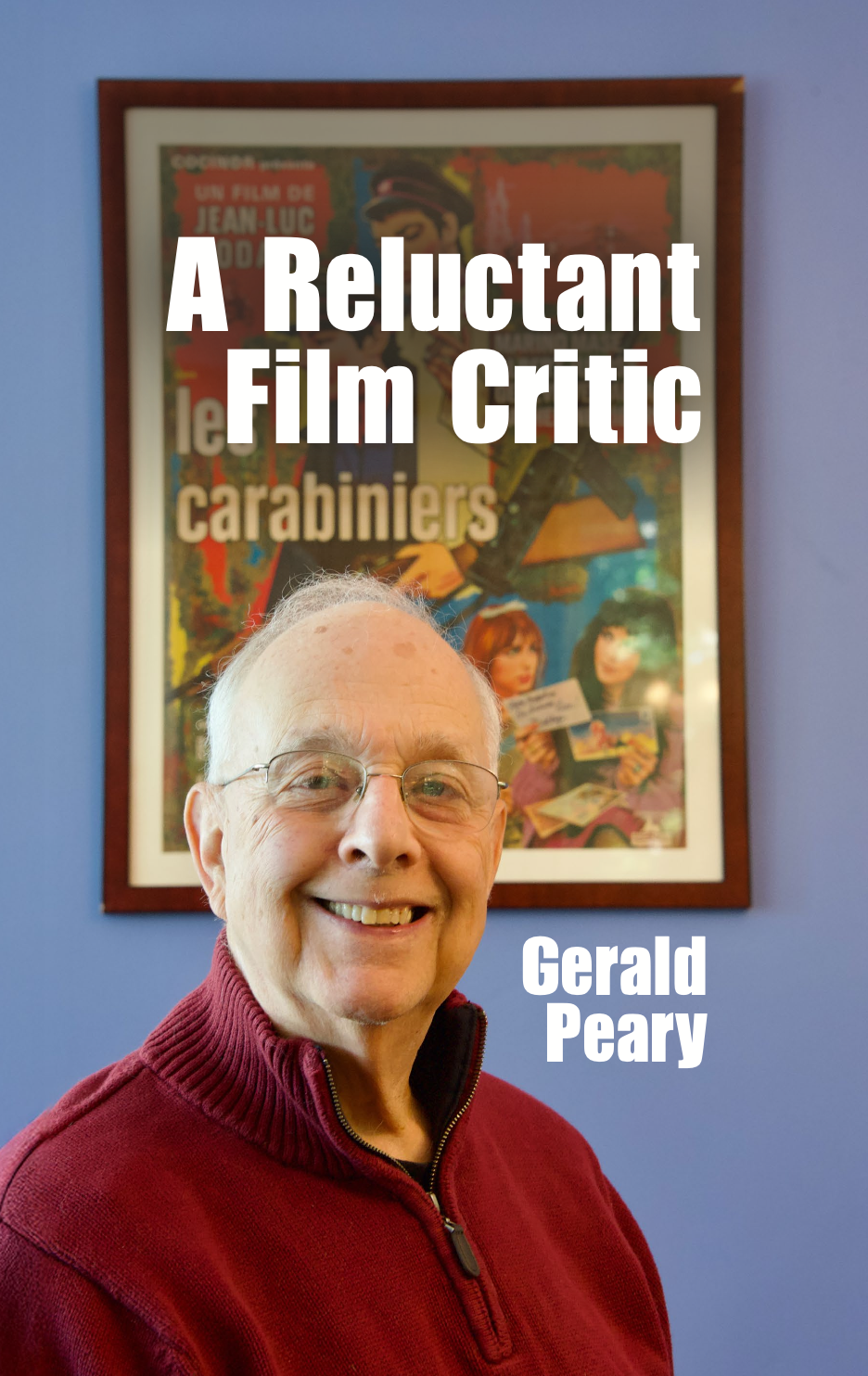

A sharp, funny, and deeply engaging memoir, A Reluctant Film Critic traces Gerald Peary’s unlikely journey from a bookish, movie-obsessed boy in small-town America to one of the country’s most distinctive critical voices. Told in vivid, fast-moving vignettes, it’s a story of curiosity, rebellion, and discovery—of a life spent both inside and outside the darkened cinema. EatDrinkFilms is proud to present an excerpt from the fascinating interview by Bill Marx that concludes the book.

Bill Marx: It’s a bit daunting trying to figure out how to frame an interview about a lifetime of moviegoing.

Gerald Peary: A few years ago I was asked to do a stage interview with composer Philip Glass about the music he’d provided for various films. I was very anxious as I’d never met Glass before, so I wanted to know from him precisely what he wished discussed, what film clips he was comfortable with, and in what order to show the clips. And Glass replied, “Let’s wing it. Whatever movie clips you want to show, that’s fine with me. Ask any question you want, that’s also fine with me. Surprise me!” It turned out to be a great evening because it was spontaneous and Glass had lots of fun having no idea what I was going to throw at him. So, surprise me!

Gerald Peary: A few years ago I was asked to do a stage interview with composer Philip Glass about the music he’d provided for various films. I was very anxious as I’d never met Glass before, so I wanted to know from him precisely what he wished discussed, what film clips he was comfortable with, and in what order to show the clips. And Glass replied, “Let’s wing it. Whatever movie clips you want to show, that’s fine with me. Ask any question you want, that’s also fine with me. Surprise me!” It turned out to be a great evening because it was spontaneous and Glass had lots of fun having no idea what I was going to throw at him. So, surprise me!

All right, we’ll just go into it and see what happens. Could you talk a little bit about when you first embraced cinema?

I was always, always deeply into movies. From early childhood. In contrast, critic colleagues have told me that they didn’t care about cinema until they took an inspiring film course in college, or at 19 they read Pauline Kael and fell head over heels with her writing and her opinions, or they saw Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel dueling about movies on TV and that made them want to be cinephiles. But I was film crazy from probably 5 years old when I was a child living in the hills of West Virginia in rural America. I frequented two theaters on the Main Street of Philippi, the small town where we lived, especially the one which regularly showed “B” Westerns.

I’ve written several times about seeing my first movie at 3, around 1947–1948, a live-action Goldilocks and the Seven Bears. I was completely enraptured, especially by a scene in which the characters, human and animal, had a pillow fight, and feathers from the pillows soared in slow-motion through the air, a moment akin to that with the schoolboys in Jean Vigo’s 1933 surrealist masterpiece Zéro de Conduite.

But seemingly the film that I am confident I watched does not exist! I wrote an essay for a book about this seminal cinema experience and the editor of that book, film critic Peter Keough, decided to fact check. And he was shocked, chagrined, amused or whatever because he could find no record anywhere of this film that I was raving about. An animated “Goldilocks” yes, but absolutely no live action version. But I know that film is out there…

At least in your own head.

It’s more than my head! Someday a print will be found in the dusty basement of some film archive and I will be vindicated!

I want to probe a little bit your initial attraction to cinema. Pauline Kael has made the case that early moviegoing for her had an element of the illicit, “I’m seeing something that my parents would not want me to see.” Was moviegoing illicit or delinquent in any way for you?

Do you mean when I was 13 and blushing at the ticket booth paying to see Brigitte Bardot’s nakedness in And God Created Woman [1956].

Or my embarrassment as a teenager sneaking into some soft-X pseudo-documentary with bare-breasted nudists playing volleyball?

I mean when you were still a child.

Then the answer is “no.” My parents never said, “You can’t see certain movies.” They never censored me in any way. They had no interest in the illicit, no knowledge of the illicit. But they believed that whatever your kid wants to do is okay. So I was seeing whatever movies I wished to see and I was reading whatever books I wanted to read and that was fine with them. No guilt.

But if not illicit, going to movies as a young child was certainly a thrilling adventure. In the early 1950s, children like me went all by themselves to the cinema, which is just unimaginable in our time. The cinema was a safe place. Even my worrywart Jewish mother didn’t think that somebody seedy was going to molest me or kidnap me. So there was something alluring and sexy about being a little boy sitting alone in a movie theater. And gasping at what was up there on the big screen.

Are you describing the education of the future film critic or a fan? Movies obviously reflected a reality that you were not living. You had that fantasy of seeing the adventurous heroes, glamorous starlets and so forth, which must have been pretty attractive, right?

I don’t know that I saw things differently from others. Everyone likes cute starlets and screen adventures. I was just part of the crowd, and whatever I was seeing was pretty appealing to me. Unless it was adults on screen talking too much and too much kissing. But I was placated as long as there was filmic activity, like cowboys galloping on horseback across the range or Native Americans whooping it up with bows and arrows. I adored swashbucklers, Three Musketeers types of stories with lots of sword fighting. I loved guys with feathered hats stabbing each other with pointy swords! That was great.

The beginning of the 1950s was still an era when there were serials at the movie theaters, at least in rural West Virginia. And that, for me, was a primal surrealist experience. Seeing people tumbling from skyscrapers or into crocodile-filled waters and having people blown up by dynamite and almost drowning in floods, and things just swirling around you! Just a constant super-adventure with scary things happening to the characters every second. Wow!

I felt that delirious spirit again years later with early James Bond movies like Dr. No [1962] and Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler [1922].

Georges Franju certainly captures that spirit with his homage to serials, Judex (trailer) [1963]. And Spielberg did all right by me with Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

Did you become more interested in movies than books? Though you’re an avid reader, did movies win out in that competition?

I don’t think they won out. My whole life, I’ve been schizoid, jumping between the one medium and the other. Even now I ask myself several times each day, “Should I read a book or see a movie?” I sometimes say that if I were on that proverbial desert island, I would take a book over a film. Books probably win, but it’s really, really tight. But what a wonderful choice: do I open a book or do I watch a movie on my computer? Or do I listen to music—jazz or country or rock—or see a Boston Celtics basketball game on TV? I was not bored as a child and I’m never bored as an old person because of all these grand choices open to me without my leaving my house.

Did you watch movies naively as a child or did you begin to develop a critical sensibility?

My first moment of a critical sensibility was when I realized that serials were often a fraud. If you saw a serial one week, the ending showed that it was impossible for the characters to escape the peril they were in. Death was imminent. But the following week when you saw the final scene repeated at the beginning of the serial’s new chapter, you noticed the insertion of a couple of shots which allowed the characters to get free. And live on. I correctly felt cheated.

You felt you’d been fooled and you were pissed off. The beginning of the critical impulse. Did you decide after that you’d have to look at movies far more carefully?

I doubt if at 7 or 8 I had that conscious thought, but I got that movies weren’t perfect. They were just romantic objects. They had flaws like everything else. And obviously later as a critic I saw many flaws in movies and realized that movies were rarely perfect.

Besides Westerns and swashbucklers, what other kind of movies did you like as a kid?

Stupid comedies for sure. Abbott and Costello and the Bowery Boys were just phenomenal. That goofy Huntz Hall! A bit later, Jerry Lewis and Danny Kaye.

When puberty hit, I assume you became interested in the sexual elements in films.

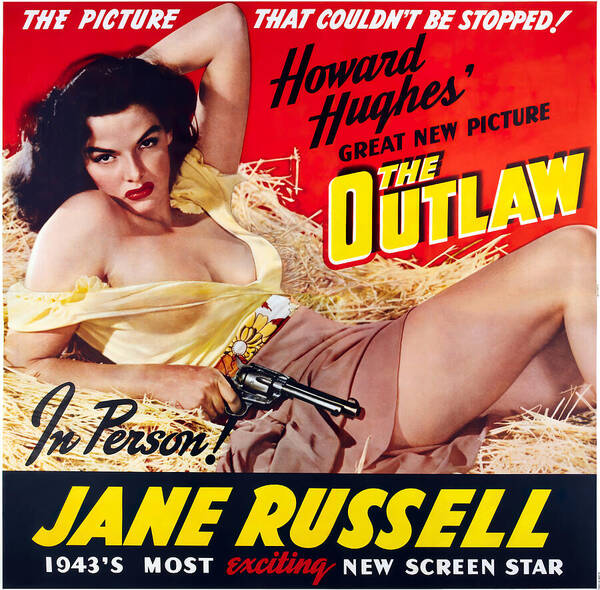

Certainly by age 12 I was aware of attractive women in films. My male gaze was afire! I first noticed Virginia Mayo, that leggy blonde actress, and I remember staring hard at a poster outside a theater of bosomy Jane Russell.

And I felt an erotic tingle seeing Anne Francis prancing about barefoot and in the shortest skirts in Forbidden Planet [1956] and shapely Julie Adams bobbing in the water in Creature from the Black Lagoon [1954]. Was I some kind of a fetishist? I was taken by Grace Kelly in a slip in Dial M From Murder [1954] and Elizabeth Taylor also in a slip shedding her stockings in Butterfield 8 [1960]. So yes, I felt the sexuality of movies and I liked that. I still like that: Eros and cinema.

You do realize you aren’t being politically correct, tooting your own horn about your heterosexual desire?

I can’t deny that it’s part of my sensibility, including when I’m reviewing films. I think it’s absurd that male heterosexual desire is dismissed in our PC age as having no validity, or for being intrinsically creepy. But having desire isn’t the same as acting out in life as a sexist pig, which is not acceptable. Anyway, I’m for most kinds of sexual desire being expressed in cinema and not repressed, and that includes queer desire and trans desire. Some favorite films of mine are manifestations of queer sexual sensibilities from Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’amour [1950] to Rose Troche’s Go Fish [1994] to Pedro Almodóvar’s Law of Desire [1987].

Besides becoming sexually aware, did your taste in movies become more sophisticated when you were 12 and 13?

My taste expanded to horror films and crime movies. But as a teenager I was not suspicious at all of costume dramas, one of the funkiest and campiest of genres. I didn’t notice anything funny or stupid when I saw The Ten Commandments [1956] or Ben-Hur [1959], two movies which I now find absurdly bad. My favorite costume drama by far was Land of the Pharaohs [1955], a disparaged film which I still enjoy. I understand it was also a Martin Scorsese childhood favorite, though neither of us were cognizant that it was co-written by William Faulkner and directed by Howard Hawks. When I really adored a movie, I would see it three or four days in a row. Land of the Pharaohs was one of those pictures I watched repeatedly. This viperous woman played by Joan Collins screws around on her pharaoh husband and he locks her alive in a closed-off pyramid to die. What an inventive revenge!

Yes, one of the great death scenes with the sands slowly moving room to room in the pyramid. To bury Joan Collins forever.

That was mind-boggling. For Land of the Pharaohs, we’ve got to thank Faulkner for writing some of the scenes, maybe that scene.

Were you talking to other kids as you’re watching these movies? Were you saying to others, “Here’s what I think, what did you think?” and beginning to have a critical dialogue about the cinema?

When I was 12 and now living in Columbia, South Carolina,

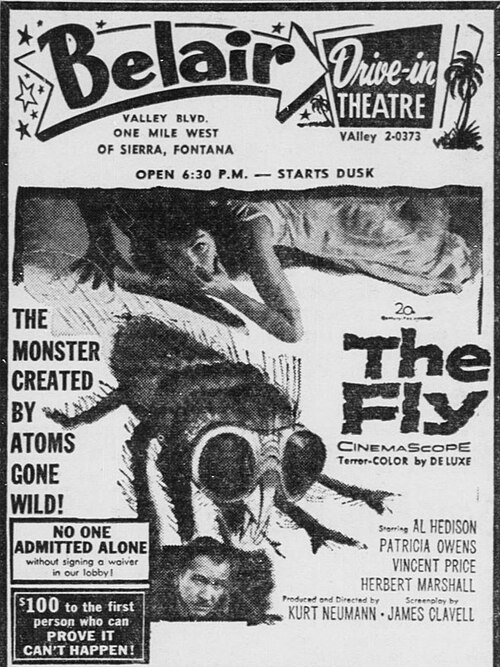

I had a friend, David, who was also a movie fan. David and I took the city bus to see films on Saturdays, and usually we gravitated to horror movies. We were lucky enough to see the original runs of The Incredible Shrinking Man [1957] and The Fly [1958] and Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1956]. But did we talk critically about these movies? I doubt it. We were just fans.

The other person I saw movies with was my little brother, Danny Peary. He was five years younger than me. Sometimes I didn’t want him around because he was an annoying younger brother. But we did see Land of the Pharaohs together, for sure. And we saw the most important movie of both of our childhoods, John Ford’s The Searchers [1956]. I watched it when it first came out in summer 1956, which would make me 11. And my brother, who was 6, came along for three or four days in a row. I’m sure we didn’t have critical discussions, though Danny also grew up to be someone who wrote seriously about movies. Among other excellent books, he’s the author of the highly influential Cult Movies 1, 2, and 3 and Guide for the Film Fanatic. Many important filmmakers swear by Danny’s works as getting them into cinema.

Again, you talked to nobody critically about the movies you saw?

That’s correct, and certainly not to my parents. But the strange thing was that I had astonishingly developed movie taste. Where that came from I don’t know. I’ve written about this in several places, and I still scratch my head at this, but almost all the movies that I really loved turned out to be from directors who later were claimed as auteurs. That includes Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks, Nicholas Ray, Fritz Lang, George Stevens, Joseph H. Lewis… just on and on. I didn’t have the vocabulary to note camera movement or editing or any visual component or to articulate how movies were shaped. I was only dimly aware of film direction. But all I can say is that my instincts were to pick really first-rate Hollywood movies. I did go with my parents to see two favorites, Shane [1953] and Rear Window [1954]. But what other 10-year-old went by himself to see Johnny Guitar [1954]?

I know John Ford is a key director in your own personal pantheon and The Searchers is among your favorite films, so seeing it at 12 was quite a leap from those sword-fighting films you’d been lapping up. The Searchers is ten times deeper than, say, The Mark of Zorro [1940]. Did you feel, “This is the real deal”?

Swashbuckler films have almost no psychological life. It’s just witty banter and fun sword fights and pratfalls and that’s about it. But The Searchers was this disquieting movie with deep and terrible psychological things going on. It certainly was a primal viewing experience from the very first act, realizing that the Natives were going to massacre this nice family. And then watching Debbie being separated from them, crawling outside, and then the moment which scared the dickens out of me, the dark shadow of Scar falling over little Debbie and then Scar in warpaint blowing this discordant note into his horn. Debbie, a child like me and my brother, was being stolen away! I felt that in every bone and in my brain and gut.

That was very, very different, being so shaken up sitting there in the movie theater. Far from Scaramouche [1952]! Even with four viewings, it didn’t register for me to notice that The Searchers was directed by someone named John Ford. The only directors whom I was aware of when I was 12 or 13 were the two who really self-promoted, Cecil B. DeMille and Alfred Hitchcock, whose names were above the title. I knew of DeMille when I saw The Greatest Show on Earth [1952] and The Ten Commandments and Hitchcock for a bunch of 1950s films. And then Hitchcock hosted a television program. But John Ford? I had no idea where The Searchers came from. It just came out of the air.

Besides knowing of DeMille and Hitchcock, when did you begin noticing the names of directors?

Probably three or four years after The Searchers experience, when I was 15 or 16. I slowly learned of directors because I started to read film criticism. My parents subscribed to a culture magazine called The Saturday Review, and every week there was a film review column shared by Arthur Knight and Hollis Alpert. Knight was a film professor at the University of Southern California and Alpert was a New York critic. They were somewhat intellectual and at least mildly critical. I read these columns with interest. They led me to smarter Hollywood films and also some foreign-language films.

Editor’s Note: The Reluctant Critic has four sections:

A Boy Genius in the Old South

I Was a Pre-Teenage Auteurist

Sweet Memories of a Film Addict

And the interview with Bill Marx –you have just read the opening of the 68 page interview of fascinating stories about going to the movies, loving them, writing about them, and eventually becoming a filmmaker.

A Reluctant Film Critic can be ordered from Sticking Place Books (at a discount) or your favorite local bookstore or where you buy books.

Sticking Place Books is a New York-based publisher specialising in cinema, offering interview books, memoirs, critical and historical studies, screenplays, and essay collections. Our catalogue includes books by and about Guillermo Arriaga, Charles Chaplin, Damien Chazelle, Larry Cohen, Brian De Palma, Jonathan Glazer, Michael Haneke, Werner Herzog, Abbas Kiarostami, Stanley Kubrick, David Mamet, Pierre Rissient, Bruce Joel Rubin, Esfir’ Shub, Preston Sturges, Peter Whitehead, Paul Williams and Caveh Zahedi. Authors published by SPB include John Baxter, Ian Christie, Michel Ciment, Peter Cowie, Daniel Kremer, Ross Lipman, Scott MacDonald, Joseph McBride, Leonard Maltin, Patrick McGilligan, Adrian Martin, James Naremore, Gerald Peary, David Robinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum and David Sterritt.

More clips and trailers for films mentioned can be viewed below.

Gerald Peary has been a much-published film critic in Cambridge, Massachusetts for more than 45 years, writing for the Real Paper and Boston Phoenix and now the online magazine, The Arts Fuse. His articles have appeared in international cinema journals including Film Comment, Film Quarterly, Sight and Sound, Cineaste, Positif, and The Velvet Light Trap. He is the author or editor of nine books on cinema, and the writer-director of three feature documentaries, For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism (2009), Archie’s Betty (2015), and, with Amy Geller, The Rabbi Goes West (2019). He has served on film juries around the world, including Venice, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Rotterdam, Edinburgh, Moscow, Locarno and Buenos Aires. He acted in the 2013 feature film Computer Chess. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Gerald Peary has been a much-published film critic in Cambridge, Massachusetts for more than 45 years, writing for the Real Paper and Boston Phoenix and now the online magazine, The Arts Fuse. His articles have appeared in international cinema journals including Film Comment, Film Quarterly, Sight and Sound, Cineaste, Positif, and The Velvet Light Trap. He is the author or editor of nine books on cinema, and the writer-director of three feature documentaries, For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism (2009), Archie’s Betty (2015), and, with Amy Geller, The Rabbi Goes West (2019). He has served on film juries around the world, including Venice, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Rotterdam, Edinburgh, Moscow, Locarno and Buenos Aires. He acted in the 2013 feature film Computer Chess. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

All of his books listed here.

Peary’s website is archived on The Wayback Machine.

A sampling of reviews and feature articles.

Enjoy clips and trailers for movies Peary mentions above as being influential favorites as a budding film lover. The images accompanying this excerpt are not in the book and have been posted by the editor of EDF.

Listen carefully to hear who is the narrator.

For even more “The End” titles look here.