An Interview with Director Julie Rubio

by Geneva Anderson

Tamara de Łempicka, the Russian-born 20th century painter known for her cosmopolitan Art Deco portraits and arresting nudes, is front and center in the Bay Area with two major Bay Area venues showcasing her: the Mill Valley Film Festival and the de Young Museum.

Orinda filmmaker Julie Rubio’s years-in-the-making documentary, “The True Story of Tamara de Łempicka & The Art of Survival,” had its world premiere at the 47th MVFF with two sold out screenings and more to come. Simultaneously the de Young Museum opened “Tamara de Łempicka,” the first major museum retrospective of the artist in the U.S. It runs through February 9, 2025. (Details at the end of the article.)

After watching a screener of Julie Rubio’s doc, I couldn’t wait to interview her about making the film and about Tamara de Łempicka, a remarkable woman and a dazzling talent who has long been controversial in the art world and was never given her full due, until now.

After fleeing the Russian revolution in 1917, Tamara de Łempicka landed in Paris, where she cultivated an elite social circle and became the talk of the town for her coveted modern portraits and her glamorous and flamboyant lifestyle. She soon became synonymous with Art Deco painting, which had its zenith in the interwar period. Her large body of work included commissioned portraits; paintings of her family, lovers and friends; and masterful drawings. Based on a foundation of superb draftsmanship and a mastery of dramatic lighting, her chic signature style was characterized by vibrant metallic hues, bold geometrics and an icy vibe. She understood sensuality and painted women in elegant couture gowns that fit like a second skin. Her female nudes were unique; they were provocative but absorbed in their own thoughts and pleasure and thus had agency. While Lempicka emerged as one of the most skilled painters of her generation, her work was sidelined by many critics as decorative, and its eroticism was misinterpreted as being pandering to women.

Rubio reveals more of Łempicka’s story, presenting her life journey as one of immense creativity in the face of great disruptions and her artworks as masterpieces of modernism whose female subjects are sensual and empowered. The film peers into the haze of the artist’s past, exploring turmoil in Russia and Europe through the lens of revolution, war, survival, and her storied relationships with men and women. Drawing on family archives and previously unseen family movies, European sources, and newly discovered documents, Rubio has pieced together new facts about Łempicka’s heritage, birth name, and early life unknown to even Łempicka’s heirs. She reveals that Lempicka suppressed her true story and constructed an identity that allowed her to navigate interwar Europe as a thoroughly modern woman. The film includes a series of informative and fascinating interviews with Łempicka’s granddaughter Victoria de Łempicka and great granddaughters Marisa and Cristina de Lempicka, curators, gallerists, journalists, and singers portraying her on Broadway and showcases the celebrities who collect her. What emerges is a beautifully crafted film that is part family history and part art history.

Tamara de Lempicka, photographed at her easel at King Vidor’s Barrymore Estate, 1940, painting “Suzanne au Bain.” (Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

Describe your first encounter with Tamara de Lempicka’s artwork

Julie Rubio: It was in the 1990’s, in Miami, at the Americana Hotel. There was a small exhibition, it was just copies, but it really grabbed me—the bold colors, striking figures, and compositions. I’d never seen anything like that before. When I learned that she was painting in the 1920’s I couldn’t believe it; it seemed so contemporary.

Learning that she was bi-sexual struck a deep chord with me too. I went through some anxiety. I’d grown up in a small town in Southern California and didn’t know anyone who was bi-sexual or gay. I was told that bi-sexuality didn’t exist—you were either gay or straight. I realized that, when I’d been exploring my own sexuality, I’d actually had girlfriends and been in love with a girl. I learned that Lempicka had two marriages but that many of her models were her lovers and that her longest love was a 30-year relationship with Ira Perrot, a woman who was her best friend. Through Lempicka’s life story and her art, which depicts women together so intimately, I realized that I am bisexual. I’ve been married happily to Blake Wellen for 18 years now and it’s monogamous and I’m happy to really know all the sides of myself.

“Autoportrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti),” 1929, oil on panel, 13.75 x 10.62 inches, Art History Project

How did you get connected with the Łempicka family?

Julie Rubio: I’d made a short film, “Impression,” about Degas’ painting “The Rape” (1868-1869) (also known as “Interior.”) which has been an enigma because it’s such a creepy painting, depicting a very intense moment in a darkened bedroom between a fully clothed man and a partially dressed woman who has been raped. A friend of mine who worked at the Weinstein Gallery in Union Square saw the film at a festival and offered to introduce me to Lempicka’s grand and great granddaughters who were coming to the gallery for a small exhibition of their grandmother’s work. She mentioned they were looking for a writer for a narrative screenplay and a female director. I met with them and learned they had sold the rights but wanted to make a film. A lot happened next—Victoria, the granddaughter, and I started to write a screenplay together but a flood destroyed a lot of the material; then they sold the rights again; then Covid struck. Amy Harrison, a former board member of Women in Film (WISFBA) of which I am president, suggested that I make a doc and bypass the constraints that a narrative film imposed. The family agreed that a doc was the best solution during a lockdown and we began working in 2020, in the middle of the pandemic.

So this entire process of getting to the point of deciding what type of film and drawing up a contract took how long?

Julie Rubio: Just over 20 years now. Meanwhile, I made “East Side Sushi” (2014) and other films, and did a show, and was very busy working, but I never put aside the dream of this film.

Were the family and sources you used forthcoming with information and archival materials?

Julie Rubio: Yes. My biggest concern going into this was making sure the family understood that this is a doc which is completely different from a narrative film which they’d been focused on. They didn’t get a say in crafting what interviewees say. I let them know that I was going where the story takes me and it’s not always going to be what you want to hear and the way you want it because people have their own opinions. They agreed but, of course, there were times when we hit heads. They recently watched the final cut and loved the film. I was told “Tamara is giving you her blessing from above.” That felt good.

Are there facts that emerged in the process that were previously unknown to the family?

Julie Rubio: I had been digging for nearly 20 years. There were hints that Tamara might be Jewish, that her father was Jewish, but all I saw was a lot of mud, nothing clear. I just knew there was more to her story. The family kept telling me there’s no birth or baptism certificate. I’ve got thousands of followers on my Insta and Facebook, so, during the pandemic, I reached out to this network. Arthur Stepinski contacted me and said he lived very close to the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw where her family was buried. Marissa, the granddaughter, said nobody knows that. He was persistent and braved -4°C weather to send photos of the graves of Bernard and Clementina Dekler, her grandparents. This was the grandma mentioned in the film who was so devoted to Tamara and who really empowered her. When I told the family, everyone got goosebumps. I then got another reach out from Monika Krajewska, a Polish television journalist from Discovery, who said she had proof, a publication, that showed that Tamara’s mother and father had converted from Judaism to Calvinism. She proposed to trade this information for my footage from the cemetery. I was initially suspicious, but I was thrilled when she agreed to be interviewed for the film. Her ability to break down the publication with such expertise truly exceeded all my expectations. Then, two years ago, someone posted on FB that Tamara had a different birth name and birthdate. When I told the family that I thought a birth and baptism certificate had surfaced, they confirmed it. Having seen the documents, I still needed to trace them back to their origin. Archivist Andrzej Slowicki confirmed she was Jewish. It’s been a huge revelation to the family that Tamara was lying, hiding things, because, she was trying to protect her family from persecution and the horrors of the Holocaust. This cast her in a completely different light.

Digging for the truth and seeing these old records is a real jewel in the film.

Julie Rubio: If it wasn’t for Arthur, Andrzej, Monicka, and the family, I couldn’t have pieced all this together. Tamara Rozalia Gorska, born May 16 1898, was really Tamara Rose Hurwitz, born June 16, 1894. You’d be amazed at how many art historians cling to her old story, using the wrong name and birthday. When I showed my film to the curators at the de Young, they immediately wanted to include it in the exhibition. I was credited in the Yale University Press exhibition catalog and co-curator Gioia Mori, the leading expert on Lempicka, further credited me in articles where she was used as a source.

Are there any further mysteries surrounding Tamara you hope to clarify?

Julie Rubio: Things are just coming out now suggesting there may be even more to this “true story.” I have documentation and the family has confirmed that she was born in Russia. I was told she was born in Moscow but it could well be St. Petersburg. We’re not sure. I’ve been told that her first husband, the aristocrat Tadeusz Łempicki, wasn’t really jailed during the Bolshevik Revolution. This would refute her scouring prisons and helping to secure his release. I’ve got people who are “sure” they know something and it turns out they don’t.

“Portrait of Marjorie Ferry” 1932, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 25 5/8 inches, ©Tamara de Lempicka Estate

Your inclusion of auction sales data for female artists and commentary from gallerist Rowland Weinstein is important and so fascinating. Money is the bottom line, isn’t it?

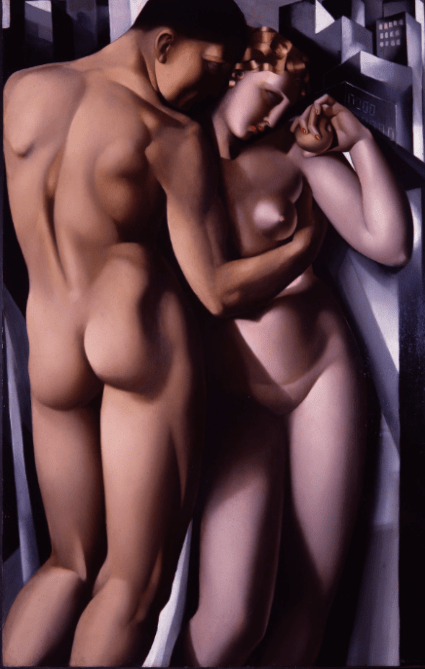

Julie Rubio: Yes, money talks. It was critical to document the state of the market for female artists’ works and the tremendous gulf between the prices commanded by male and female artists at auction. Łempicka has the third highest auction sales price among female artists, after Georgia O’Keefe and Frida Kahlo. Her rise started in March 1994, when Barbra Streisand’s collection of Art Deco and Art Nouveau was auctioned by Christie’s, London, and “Adam and Eve,” sold for $1.98 million. In 2020, Lempicka’s “Portrait of Marjorie Ferry” (1932) sold for $21.1 million at Christie’s London, setting a new auction record for her. And three months earlier, “The Pink Dress” (1927) sold for $13.3 million at Sotheby’s, NY. It’s still true that you can buy an artwork by a female artist for far less than a male artist and it’s become a good business move. Rowland now invests in female artists because he recognizes they are significantly undervalued. He understands that by holding onto their works, he stands to make a substantial profit in the future.

“The Refugees (of Spain),” no date, oil on panel. 21 1/4 x 19 5/8 inches, Musee d’art et d’histoire Paul Eluard, Saint-Denis, France

Discuss an artwork of hers that reveals something about herself that she kept hidden.

Julie Rubio: We now know that, despite outward appearances, Tamara was tormented by the events that transpired during her lifetime. “The Refugees,” painted in the 1930’s, is one of her important paintings that reveals her personal struggle when fascism was on the rise and Europe was in upheaval. She lost her first country, Russia, during the Bolshevik Revolution and escaped as a refugee to Paris. Her second husband, Baron Raoul Kuffner, was Jewish and bi-sexual. She saw what was coming with Hitler and devised their escape plan and got out just in time, again as refugees. She lost some family in the Holocaust. She had to deal with sexism, antisemitism, ageism—all those horrible isms—and still demanded to be seen in a world that did not want to see women or Jews or LGBQAI or anything that she was. In the film, Roxana Velásquez, executive director of the San Diego Museum of Art, nails it when she says “she’s a surviving animal.” Roxanna also calls Lempicka one of “the most valued and important artists of the 20th century,” without sticking in the qualifier female.

You use Barbra Streisand and Anjelica Huston as sources. What fueled their love of Lempicka?

Julie Rubio: Barbra started collecting Łempicka as part of her love of Art Deco. She has such an incredible eye and recognized what a unique talent Łempicka was. During the pandemic, she was writing her autobiography and declined an interview but she had one of her top people assist me. She offered me high-res images of her Łempickas which were a goldmine for me. These appear in the segment devoted to her. She put a caveat on the gift; she wanted to see how she was being portrayed in the film to make sure it was accurate. I agreed, which resulted in eight months of back and forth with her right hand people through calls and email. If anyone really gets her, it’s Barbra who has owned five of her paintings, including “Adam and Eve.” At the de Young’s request, I facilitated an introduction that resulted in Barbra writing the exhibition catalog’s wonderful preface.

Why did she auction that masterpiece off?

Julie Rubio: I think it’s because she likes change and wanted to move on. She gave a real gift to the world through that because it put Lempicka on the map. Previously, she was being sold in auction house basements and her works were considered decorative art. The sale generated a lot of publicity.

Anjelica Huston in that green dress talking about Łempicka’s jewelry was a high point.

Julie Rubio: She starred as Tamara in the longest running play in LA, “Tamara: the living movie” (1984-93), which was fabulous. She wore Tamara’s jewelry and the green dress and “La Belle Rafaela” (1927) was actually on the stage. She and Jack Nicholson were together then and he ended up buying the painting. He gave her the Lempicka jewelry and the dress that she wore to the 1985 Academy Awards on the night she won best actress for “Prizzi’s Honor.” That play actually went to Broadway for a short period. Marisa, Tamara’s granddaughter, told me that Kizette (Tamara’s daughter), had written Anjelica after that and asked her if Jack or her dad, Walter Huston, might want to produce, direct or act in a film about Tamara de Lempicka. Anjelica replied “I’m sorry but I’m not working with either my dad or Jack right now. I’m going to be producing and directing my own projects.” So, here it is again—the focus on the male and not on Angelica and her directing talent. That subtle bias is so engrained. I wrote to Angelica myself explaining that the family has been trying to a de Lempicka film for over 40 years and I’m trying to get a film made myself about this important artist and I’d really appreciate her giving us access to her audibles, which was granted right away. I am forever grateful to these powerful women who reached over the wall and helped me bring this to fruition. It really is a wall.

Your film is an antidote to the dismissiveness of belittlers, providing solid evidence from the world’s leading critics of her singular accomplishment and lasting legacy.

Julie Rubio: Women like Tamara de Lempicka are the visionaries who shape a better tomorrow through their courage, creativity, and defiance of boundaries. She was held down by certain societal mores and marginalized. If she’d been a man, all that would have mattered would have been her art, not who she was sleeping with or what drugs she was taking. Her most iconic pieces are from the 1920’s. Just imagine—they were so fresh, it must have seemed like a spaceship had arrived and brought them to earth. When you see a Łempicka you know it, you feel it, and it’s undeniable.

Does it make you want to own one of her artworks?

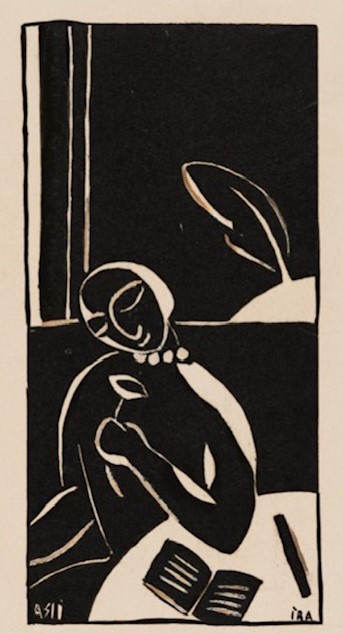

Julie Rubio: I own a Łempicka drawing which I bought from Christie’s at auction in November 2023. It’s a very small gouache and ink drawing of Ira Perrot, Tamara’s lover and dear friend for over 30 years. Christie’s dated it at 1924, but it may have been created around the time they first met. I knew it was Ira because it said “IRA” on the right and on the left, it says “ARI,” which is Ira backwards. She is wearing pearls, holding a flower and sitting with her notebook at the table. She looks kind of nostalgic. The film introduces Alaine Blondale and Yves Plantin who basically rediscovered Lempicka in 1969. Blondale wrote her catalog raisonné and Plantin had an art collection that contained this work and was auctioned at Christie’s when he died. I’ve never owned anything so precious. It’s so special because I know this story and how precious Ira was to Tamara. Nancy Couch talks about their relationship in the film. Tamara painted Ira over ten times and these portraits are some of her most iconic. The de Young exhibition’s co-curators, Furio Rinadli and Gioia Mori, asked if I would lend it and I agreed.

Your filmmaking journey seems to be exploring limitations women face and telling the stories of the rule breakers. What’s next?

Julie Rubio: It’s my hope that, standing back and taking in my work over time, it is viewed that way. So many female stories are just never told. We are not hearing 51% of the voices in the room. My upcoming film “One” explores themes of gender inequality and cultural sensitivity through the story of a Napa Valley Latina’s experience at Harvard University. She experiences a complete imbalance in the classroom attention given male and female graduate students where seminar participation is a huge component of the grade. Female students were graduating with less honors recognitions than males which impacted their early careers. The film looks at a solution while pointing out that girls and women internalize this bias, and it has had a detrimental impact on our society.

Julie Rubio and coproducer/husband Blake Wellan at the de Young’s “Tamara de Lempicka” lender reception, Thursday. At left, Lempicka’s masterpiece, “Portrait of Ira P.” (1930), which includes the hallmarks of her signature style—Ira is in a white satin gown painted so exquisitely it becomes her skin, revealing her as though she were nude. Her billowing red shawl, a marvel of air-born folds, adds a pop of color that balances the composition. She is turned toward the viewer but her gaze and mind are elsewhere.

“The True Story of Tamara de Łempicka & The Art of Survival,” screens at San Francisco’s Roxie Theater, 3117 16th St., October 26, 1 p.m. Expected guest: director/producer/writer Julie Rubio. More info here.

The de Young Museum opened its exhibit “Tamara de Łempicka,” on Saturday, Oct 12 with a special afternoon conversation at 1 p.m. with co-curators Furio Rinaldi and Gioia Mori and Łempicka’s grand and great granddaughters, Victoria and Marisa de Łempicka, a book signing and short film. This is the first major museum retrospective of the artist in the U.S., presenting 60 paintings and 40 drawings, lent from all over the world. It includes Lempicka’s post-Cubist work in 1920s Paris, her famous nudes and portraits as well as the still lifes and interiors she created in her final decades in the U.S. and Mexico. It runs through Feb 9, 2025. The de Young screened Julie Rubio’s film on January 1, 2025.

Also read Noma Faingold’s “The Diva of Art Deco.”

Geneva Anderson is a free-lance writer based in rural Penngrove, CA who writes on art, film, food, identity, and cultural heritage. She is the editor of ARThound, an online arts publication. She grew up on a small farm in Petaluma, CA, with animals and gardens. A graduate of UC Berkeley, Princeton, and Columbia School of Journalism, she covered the transition of Eastern Europe from state socialism and reported for seven years from Central and Eastern Europe, the Balkans and Turkey. She has also worked on assignment in Asia, Cuba, Mexico, South America.

Geneva Anderson is a free-lance writer based in rural Penngrove, CA who writes on art, film, food, identity, and cultural heritage. She is the editor of ARThound, an online arts publication. She grew up on a small farm in Petaluma, CA, with animals and gardens. A graduate of UC Berkeley, Princeton, and Columbia School of Journalism, she covered the transition of Eastern Europe from state socialism and reported for seven years from Central and Eastern Europe, the Balkans and Turkey. She has also worked on assignment in Asia, Cuba, Mexico, South America.

She has written or done photography for Art, Arte, ARTnews, The Art Newspaper, Balkan, Balkan News, Budapest Sun, EatDrinkFilms, Flash Art, Neue Bildende Kunst, Sculpture, EIU, Euromoney, The International Economy, The Press Democrat, The Argus Courier,Vanity Fair, Global Finance, and others. She is passionate about Rhodesian Ridgebacks and currently has two, Frida and Ruby Rose.