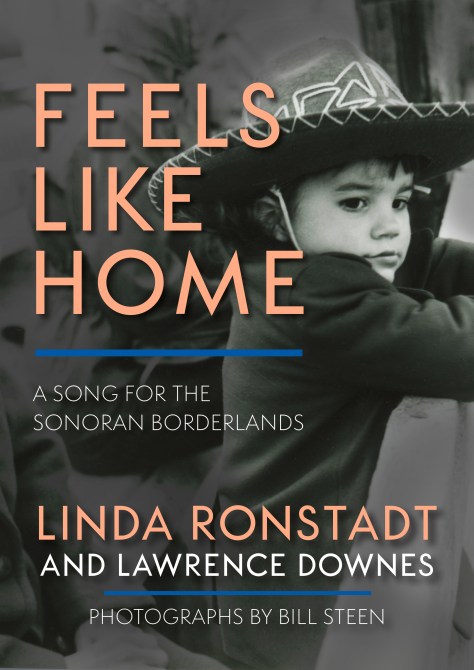

By Linda Ronstadt and Lawrence Downes, with photographs by Bill Steen

(July 14, 2023)

Growing up the granddaughter of Mexican immigrants and a descendant of Spanish settlers near northern Sonora, Ronstadt’s intimate new memoir celebrates the marvelous flavors and indomitable people on both sides of what was once a porous border whose denizens were happy to exchange recipes and gather around campfires to sing the ballads that shaped Ronstadt’s musical heritage.

Following her best-selling musical memoir, Simple Dreams, this book seamlessly braids together Ronstadt’s recollections of people and their passions in a region little understood in the rest of the United States. This road trip through the desert, written in collaboration with former New York Times writer Lawrence Downes and illustrated throughout with beautiful photographs by Bill Steen, features recipes for traditional Sonoran dishes and a bevy of revelations for Ronstadt’s admirers. If this book were a radio signal, you might first pick it up on an Arizona highway, well south of Phoenix, coming into the glow of Ronstadt’s hometown of Tucson. It would be playing something old and Mexican, from a time when the border was a place not of peril but of possibility.

This excerpt from Feels Like Home: A Song for the Sonoran Borderlands by Linda Ronstadt and Lawrence Downes is reproduced with permission from Heyday.

It is amazing that a place so roasted by sunlight and heat can summon life in such variety and abundance. The Sonoran Desert is fierce and forbidding, but it is also wildly, amazingly fertile; Sonoran is not the same as Saharan. In the 1930s, the geographer Carl Sauer wrote of the region: “Perhaps no other area in the New World comes as close to the physical conditions of the Old World Fertile Crescent as does this one.”

That doesn’t mean living there was easy. The Sonorans had to work hard at survival, diverting water to where it was needed and, when crops along the flood- plains were not available, roaming upland and down to hunt and forage over great distances.The historian Cynthia Radding has written about the ancient Sonorans’ habit of sharing what they had when they had it—feasting together when food was plentiful and going hungry together when it was not. The sense of mutual obligation seems to persist today. The photographer Bill Steen tells about visiting a family of farmers on the Río Sonora. He went to admire their lush garlic crop and noticed, near the riverbed, a patch of fava beans, a little large for a family plot but too small to be a market crop. They told Bill they had planted those beans for people in the community to take if they wanted.

The Sonorans’ ethic of generosity, Radding writes, perplexed the early Jesuits, whose beliefs about crops involved filling granaries and keeping ledgers and building a market economy. The Jesuit missions did not run on capitalist principles of profit, but they did a lot of trading, sending surplus crops by mule train to mining centers throughout Sonora. In more recent times, capitalist agriculture has prevailed there and everywhere, and it has brought with it today’s cheap abundance of things to eat and drink, many of them heavily processed and good at making you fat and sick. It has gotten harder to see market efficiency as a blessing and not a curse.

For many years small mills along the Río Sonora ground wheat into flour. Then the economy shifted. Sonora’s celebrated crop is now mostly grown and milled elsewhere in the state, in large-scale industrial operations that use staggering amounts of fertilizer and water in search of ever-greater output and efficiency. Banámichi’s old mill is a ruin. The property is tagged with graffiti and choked with weeds, and some of the weeds have become trees. It’s easy to taste the effects of industrialization in the tortillas and bread you get today. Modern commercial flour performs differently from the old-fashioned kind I grew up with. To me it tastes rancid. It’s the same with lard from factory-farmed pigs versus that rendered from a healthy, pasture-raised animal. We’ve paid a heavy price for convenience and mass production and global profits.

Much of the Río Sonora’s farmland has been taken over for growing cattle feed, but the river still supports some crops grown by family farmers, like alfalfa and garlic, along with the pecan and quince trees. In a few shady spots by the river, you will find bacanora stills, which are always built near springs or running water.

Self-sufficiency and sustainability can be hard to achieve anywhere, but it is especially challenging in a place where water is so scarce. And yet while rain is infrequent, in certain times of the year it arrives with ferocious power. We learned as kids to be alert for cloudbursts, even distant ones, because of flash floods. Any empty streambed, arroyo, or irrigation ditch could be dry one minute and a deadly wall of rushing water, brush, and boulders the next. That’s the desert for you—first it gives you too little, then too much, and it’s ready to kill anyone who isn’t paying attention.

But living in a harsh climate has its rewards. There’s something to be said for the way a land of extreme weather sharpens and stokes emotions in a way blander environments can’t. In blazing heat, a well-timed passing cloud or the blessed whisper of a breeze feels like an answered prayer. There’s relief and almost drunken delight when summer’s unbearable grip is finally broken by the wild monsoons of July and August, or even just when the swamp cooler on the roof kicks in and the heat indoors retreats enough for your thoughts to solidify out of boiled mush. (Swamp coolers are low-tech air conditioners that work through the cooling collision of evaporating water and very dry air. Our swamp cooler used pads made of spongy wood shavings that gave off a wonderfully sweet, fibrous, planty smell when the air flowed through them. I always loved it when my dad put fresh pads in the swamp cooler.)

Ofelia Zepeda, a Tohono O’odham poet and linguistics professor at the University of Arizona, writes beautifully about the acutely water-conscious rhythms and emotions of Sonoran life. (Her volumes of poetry include Ocean Power and When It Rains.) Even with a cloudless sky, she writes, the women of Sonora could tell when a storm was due. “It smells like wetness,” they would say, and the aroma was strong enough to wake some people from sleep. Zepeda, who grew up in Stanfield, a little town among cotton fields between Phoenix and Tucson, has also published a book on O’odham grammar, and her poems in O’odham and English are exquisite and spare, like the desert.

She tells how her mother and grandmother would cook breakfast by kerosene lamplight in the hushed dark before sunrise:

The women planned their day around the heat and the coolness of the summer day. They knew the climate and felt confident in it. . . .

To the women, my mother, my grandmother, there was beauty in all these events, the events of a summer rain, the things that preceded the rain and the events afterward. They laughed with joy at all of it.

No large human settlements, not even those of the ancient Sonorans, ever achieved some mystical or perpetual balance with nature, but it’s hard not to notice how badly out of whack things have gotten in recent times. Water in the desert tends to be treated like ore, to be extracted from the ground until it’s gone. As for mining, it has given many people in Sonora a livelihood, including my Mexican forebears, but that, too, exacts its own terrible cost. In 2014 a mine spill at Cananea made the Río Sonora flow blood-red for weeks. The heavy metals in the water spread sickness through the valley and poisoned the river sediment. There was a lot of hand-wringing afterward, and promises of compensation and reform, but many in the valley fear that little has changed and disaster can happen again.

Mexico has a long history of human-caused misery, and this part of the country is as scarred as anyplace else by old cruelties and violence. Much of it was endured by Native peoples whose existence was upended once the Spaniards arrived. In Mexico as in the United States, you don’t have to dig far to find the deep veins of racism, or to observe the acute and often toxic consciousness of social status and caste.

But goodness lives here, too. Banámichi and the rest of the Río Sonora also have an enchanted quality, an atmosphere that has always struck me as unusually peaceable and gracious. I think this has to do with the solidarity that seems to have carried on in the way Mexicans and Indigenous peoples and southern Arizona Anglos have long worked together—side by side, up and down the river, across the desert, heedless of the border, which is a relatively recent political invention. In a punishing environment like this, humans need to cooperate to survive. I saw this with my dad, who worked with ranchers and farmers all over the lower half of Arizona and across Sonora. Decency and square dealing were values he and his customers both prized and shared. I miss him. I wish I could have known more of the people in this world he and I descended from.

For more information and to purchase go here.

Linda selects music to listen to while cooking her recipes.

Information about The Sound of My Voice and where to watch it.

Lawrence Downes is a writer and editor in New York. For more than thirty years, he worked in newspapers, including the Chicago Sun-Times, Newsday, and the New York Times, where he was an editor and member of the editorial board, specializing in issues about immigration, New York City and state politics and government, disability rights, veterans affairs, and the environment.

On August 9, 2020, Downes advocated purchasing from public libraries books by conservative authors such as Sean Hannity in order to prevent others from reading them. He further suggested composting the books for worm food.” Read articles by Downes here.

Linda Ronstadt, the great-granddaughter of Friedrich and Margarita Ronstadt of Sonora, Mexico, is one of the world’s most acclaimed singers. Her six-decade career encompassed rock, folk, country, light opera, Mexican songs and American standards. She has sold more than 100 million records, won 12 Grammy awards and is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, directed by Rob Epstein, just won a Grammy for best musical film at the 63rd Grammy Awards on March 14, 2021. Website.

Bill Steen is a photographer and collaborative builder who is especially interested in combining building techniques with community-enhancing approaches to design. Athena and Bill are co-founders of the Canelo Project, through which they conduct ecological design and construction workshops in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. They live in Canelo, Arizona. Visit Athena and Bill’s Blog, The Canelo Chronicles at www.caneloproject.com. Also his oage on The Journal of the Southwest.

Bill Steen is a photographer and collaborative builder who is especially interested in combining building techniques with community-enhancing approaches to design. Athena and Bill are co-founders of the Canelo Project, through which they conduct ecological design and construction workshops in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. They live in Canelo, Arizona. Visit Athena and Bill’s Blog, The Canelo Chronicles at www.caneloproject.com. Also his oage on The Journal of the Southwest.